Three Essays on Crime Prevention

Marcelino Guerra

March, 2023

Outline

Curbing Violence with Neighborhood Interventions: Evidence from Football Fields Construction in Fortaleza, Brazil

The paper estimates the effects of an urban renewal policy that blends person- and place-based interventions on violence in neighborhoods of a large Brazilian city. The program builds football fields, invests in citizenship formation through football lessons, and improves the nearby infrastructure, affecting 32,000 children and young adults. Difference-in-differences estimates indicate that the intervention reduced homicide rates by 45-68% in treated neighborhoods, and cost-benefit analysis suggests that social benefits exceed costs within two years. Urban policies that blend person- and place-based interventions might be cost-effective alternatives to Police Services to reduce homicides.

Less Policing, More Violence: Evidence from Police Strikes in Brazil

The paper explores Military Police strikes with different intensities and lengths in two of the most populated Brazilian states to identify the causal effect of a decrease in preventive policing on violence. I show that, in this setting, deterrence had an essential role in violent behavior: the evidence regarding the police-crime elasticity for murder is as strong as -1.56. Motor vehicle theft and robbery analysis suggest that criminals preferred violent methods to achieve their goals when the probability of being caught committing a crime was very low. The quasi-experimental literature might be underestimating the effect of police presence on violent crimes, given the nonlinearity associated with this relationship.

Does Crime Relocate? Estimating the (Side)-Effects of Local Police Interventions on Violence

Most crime economics research focuses on the estimation of deterrent effects in a credible way, and displacement of criminal activities is often ignored. Also, “More cops, less crime” studies have no words on what precisely extra cops would do on the streets. This study seeks to evaluate one of the most common policing strategies in Brazil: the allocation of blitzes. This place-based intervention has well-defined policing assignments, and 2,004 interventions were precisely recorded at the census tract level in a large Brazilian city over 52 weeks in 2012. Given the geographic and temporal disaggregation of the data, it is possible to estimate the presence of spatial and temporal crime displacement. The novelty comes from the complete assessment of the impacts of a large-scale police operation and the identification of suitable displacement areas.

Curbing Violence with Neighborhood Interventions: Evidence from Football Fields Construction in Fortaleza, Brazil

The Areninhas Project

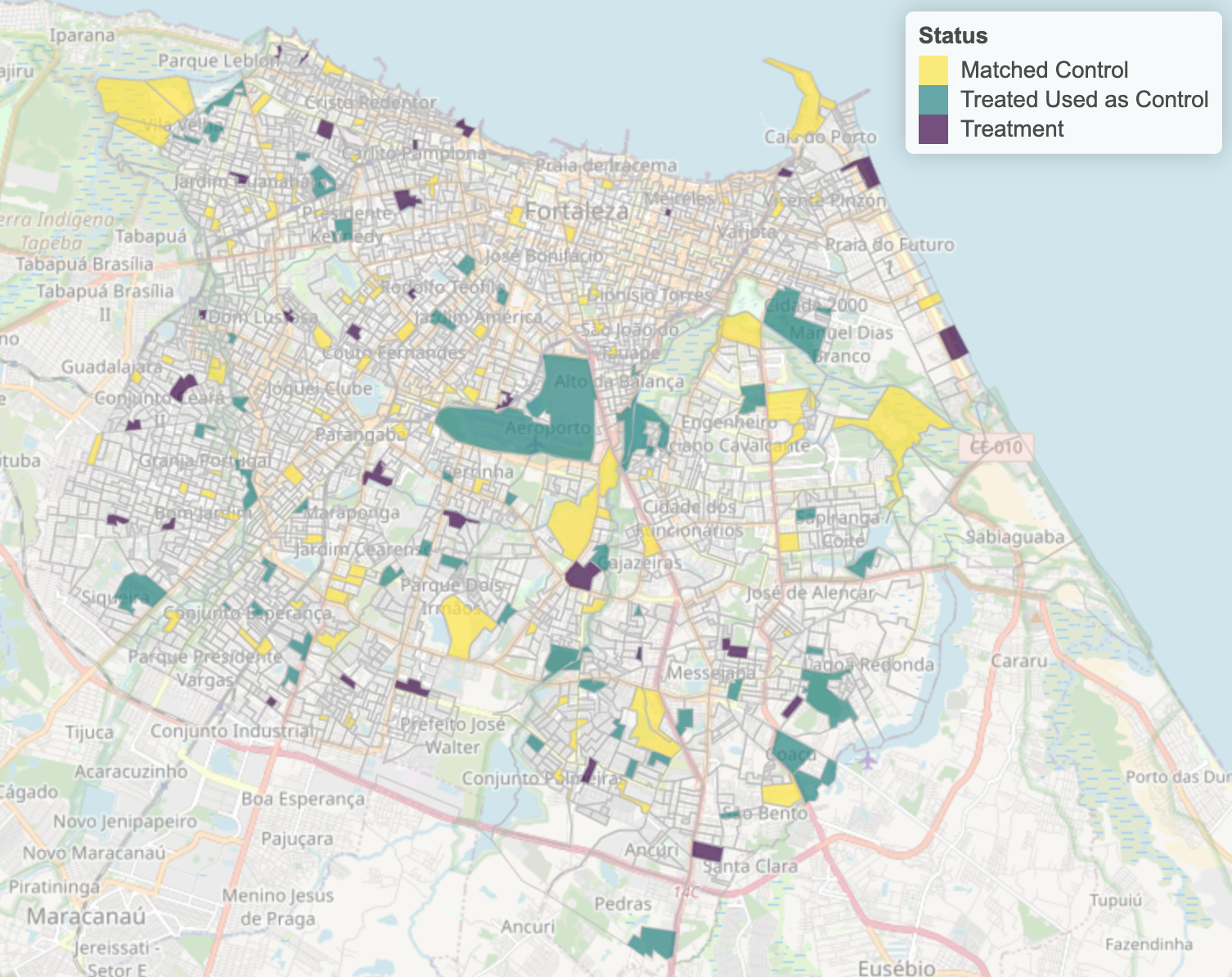

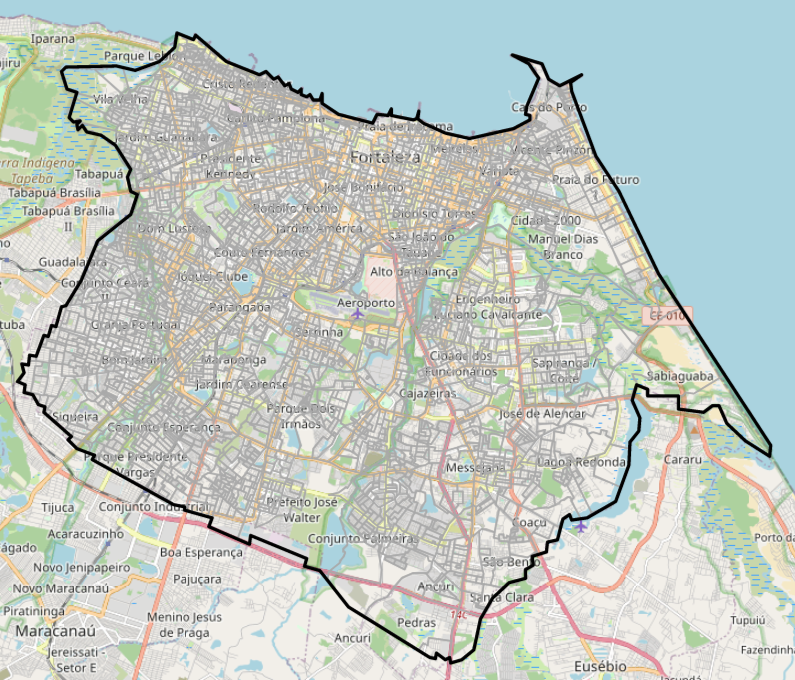

Fortaleza is the fifth largest Brazilian city and is the state capital of Ceará, located in the Northeast region of the country

The city has 120.6 sq mi of territorial area and population around 2.7 million - similar to Houston and Chicago

- From 2010 to 2020, Fortaleza’s population grew by 10%

Census 2010 divides the city into 3,043 census tracts - a.k.a neighborhoods - and 3,020 are populated

- An average tract has 812 people in 0.105 sq km

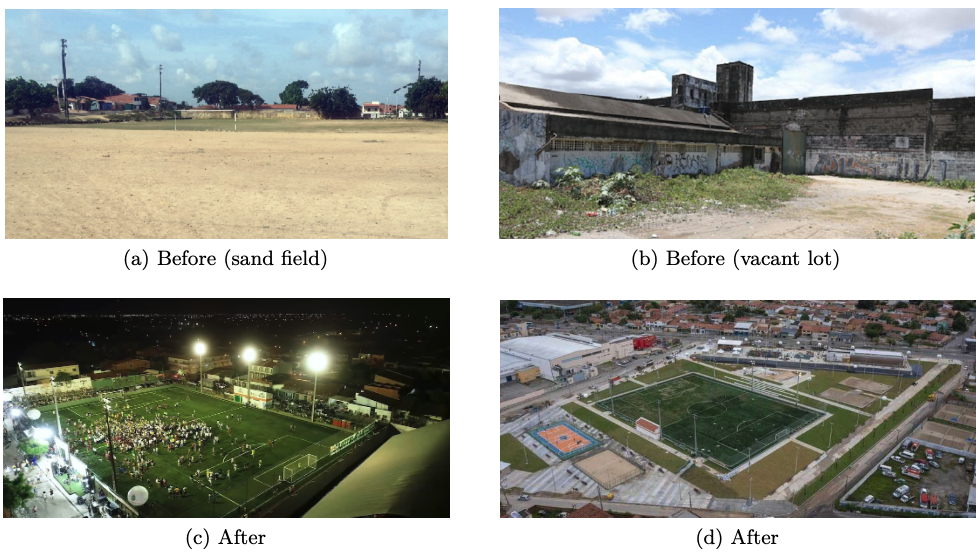

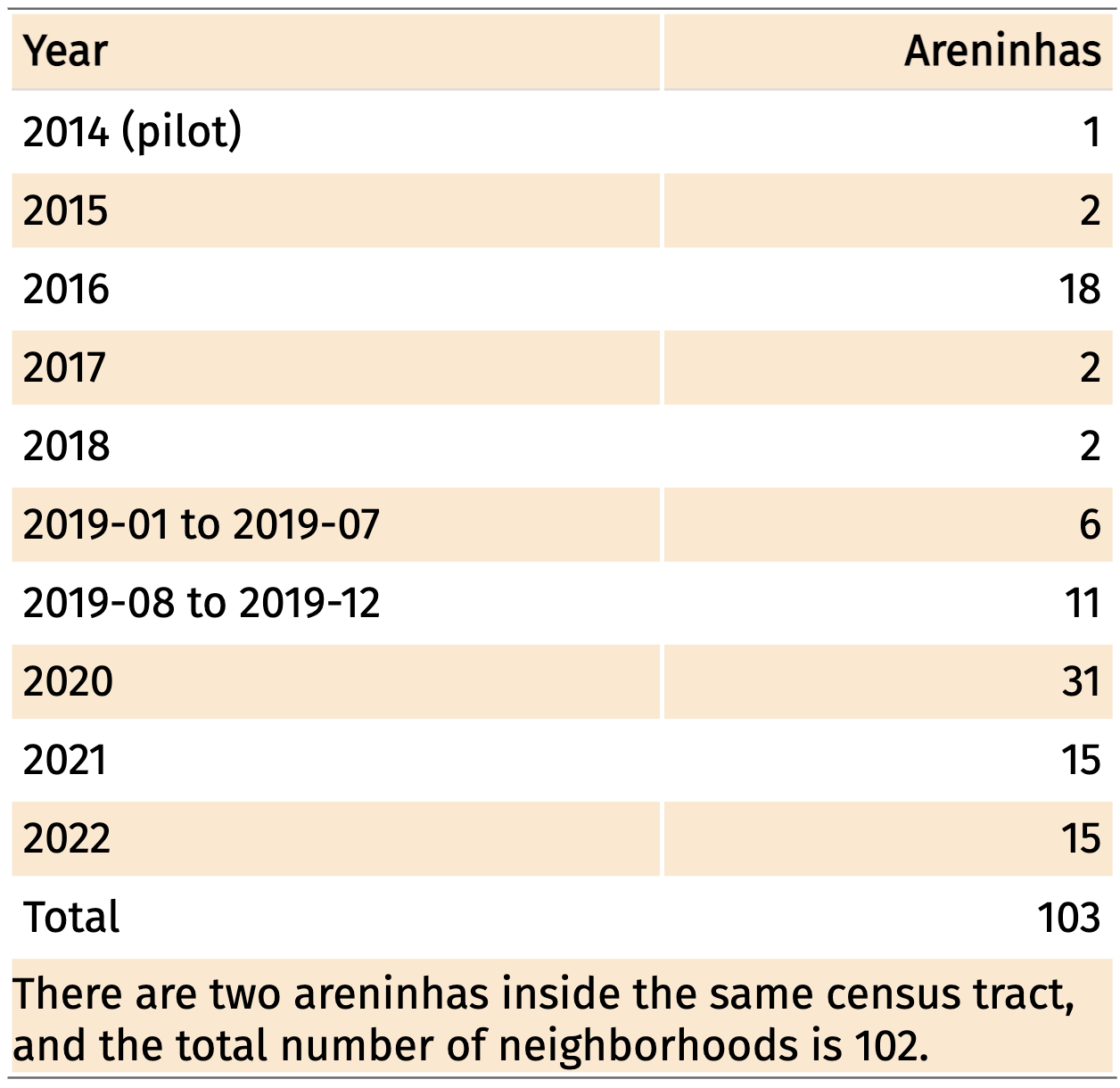

In July 2014, The City of Fortaleza began an ongoing urban renewal project called “Areninhas”

The intervention consists of synthetic football turf, a playground and an outdoor gym. The surroundings are improved with further infrastructure development

The project targets vulnerable communities and aims to provide an amenity that promotes physical activity and stimulates a sense of community

In 8 years, 103 football arenas were built in Fortaleza and more than 160 in the rest of the State

There are two types of equipment - Areninhas type 1 and 2. They differ by the size of the turf field and presence of locker rooms and bench

Each equipment have three employees. Two guards (one in the morning, one in the evening) control access to the fields, and one janitor cleans and organizes the place.

According to the City Hall, maintenance costs (salaries, energy and water) range from R$ 120,000 to 125,000/year.

Currently, 102 neighborhoods have an equipment - around 94,000 people covered

City Hall and State Government invest R$ 24.87 millions/year in four social projects: Esporte em 3 tempos, Futpaz, Esporte superação, and Atleta Cidadão

Projects directly impacts around 32,000 children

Amateur football championships are held on weekends, dance/fitness classes occur regularly, and pick-up football games happen at daily basis

Motivation

There are large disparities in health and safety between communities within a city, and local governments continue to seek meaningful policies to improve residents’ quality of life

- e.g. increase state presence - Blattman et al. (JEEA, 2021), improve street lighting - Chalfin et al. (J. Quant. Criminol., 2021), cleaning and greening vacant lots, demolishing vacant buildings, home restoration, increase in urban green space, among others - Macdonald et al. (J. Exper. Criminol., 2021) Branas et al. (PNAS, 2018), Kondo et al. (Annu. Rev. Public Health, 2018), Spader et al. (RSUE, 2016), Cui and Walsh (JUE, 2015)

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and mentorship - Heller et al. (2016, QJE), Blattman, Jamison, and Sheridan (2017, AER)

Successful neighborhood interventions are likely to generate positive spillovers, and the social benefits of the public policy might be underestimated

This study wants to evaluate an ongoing urban renewal project that blends person and place-based interventions in a large Brazilian city

Contributions

The causal effect of a citywide large-scale 8-years span urban renewal policy on violence and student achievement

- Directly affects more than 94,000 people (32,000 people from ages 7-29) and actively changes the neighborhoods’ daily routine

Exploiting the time of murders, I am able to discuss some mechanisms through which the intervention i) is curbing violence ii) is improving student performance

Assessment of the policy’s indirect impacts. Due to the research design/intervention’s characteristics, few studies can correctly identify temporal and spatial displacement/diffusion of benefits

The intervention takes place in a large and growing city in a Developing country

- Many evaluations of urban interventions are done in US legacy cities or cities in high-income countries

- It is a well–defined policy that can be replicated in Latin America and Europe

Heterogeneity analysis shows that the intervention has a larger effect on the most vulnerable population: young males with a past criminal record

The study supports a combination of place and person-based interventions to prevent public goods from turning into public bads - Albouy et al. (JPUB, 2020)

Data and Context

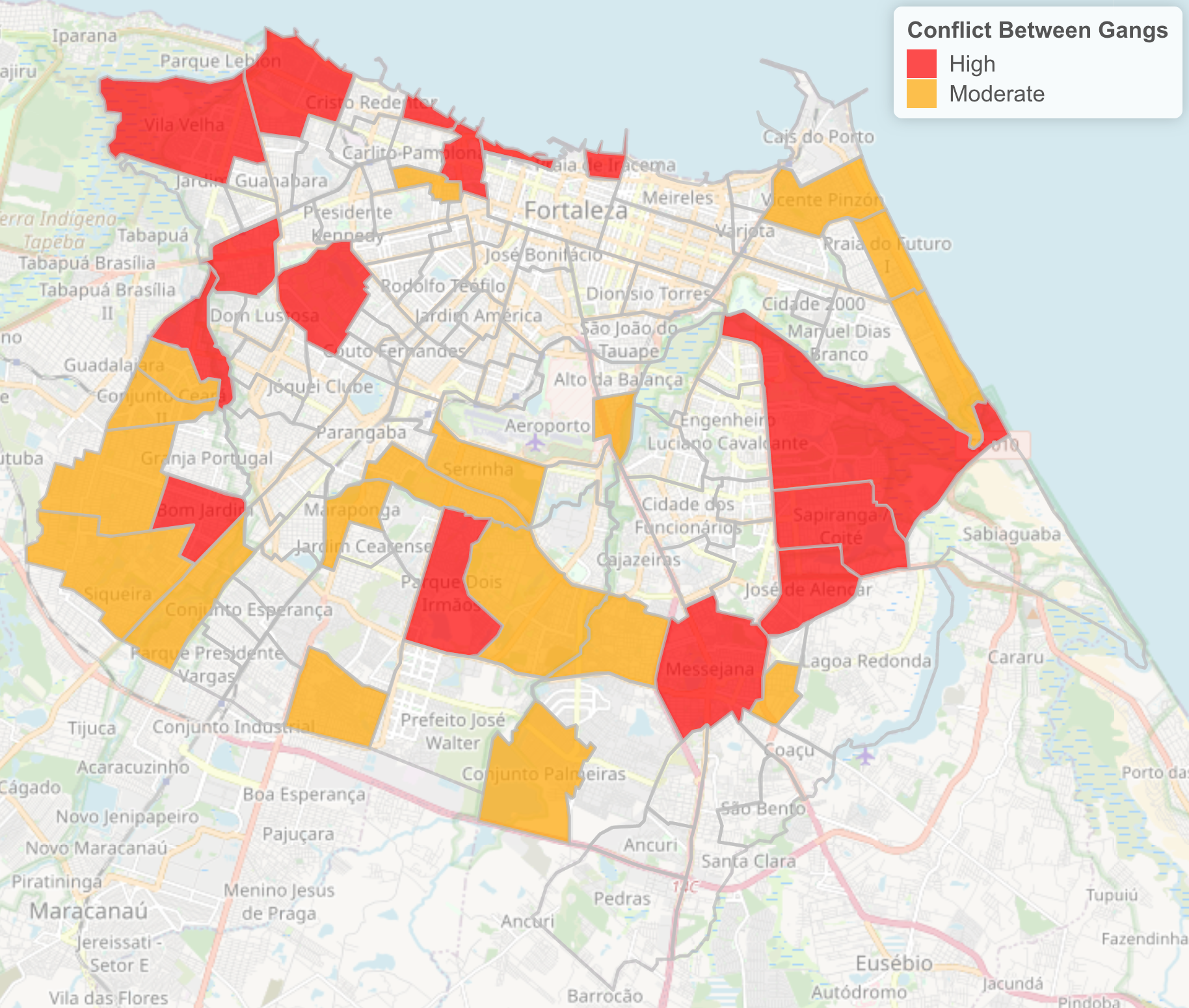

Fortaleza-CE commonly ranks as one of the most violent cities in the world, with homicide rates close to Cali-COL, St Louis-USA, New Orleans-USA, and Baltimore-USA

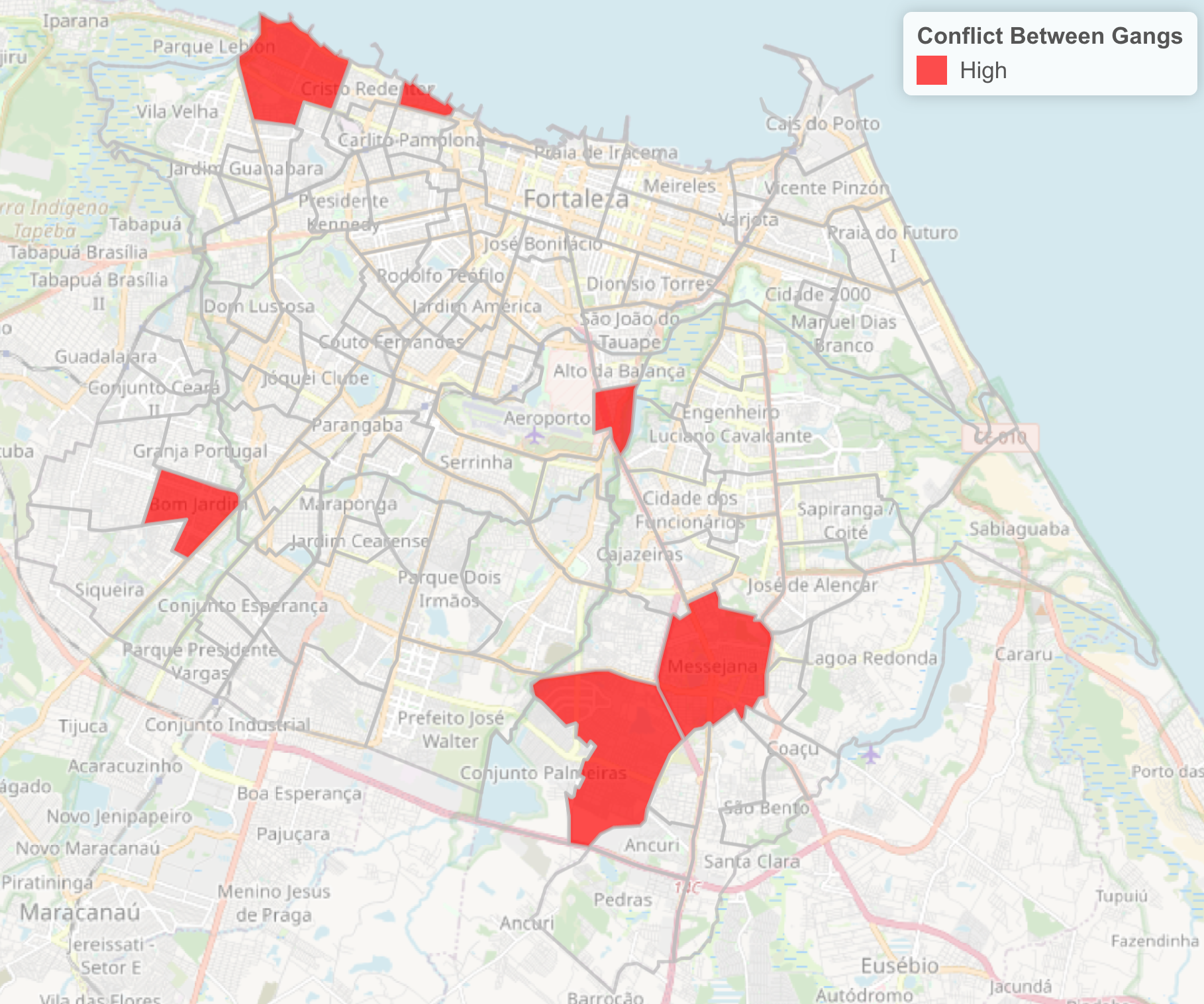

Between 2004 and 2015, homicide rates more than double. Many factors contributed to the violence escalation: from a police strike at the end of 2011 to the rise of crime syndicates

In 2019 the city managed to cut murder rates by more than 50%, compared to the previous year. However, in February 2020, the Military Police went on a general strike again, and the State went back to the top of the murder rates ranking

Detailed information about 12,081 murders within Fortaleza’s boundaries between January 1st, 2012 and November 30th, 2019

The 8,291 homicides that happened on the streets are considered in the analysis

5,560 murders occurred between 8:00 am and 10:00 pm

Murders are aggregated to months and at the census tract level. The outcome is homicide rates per 1,000 people

Note: complete addresses were converted to coordinates (lat and lon) using Google’s API

Research Design - Murders

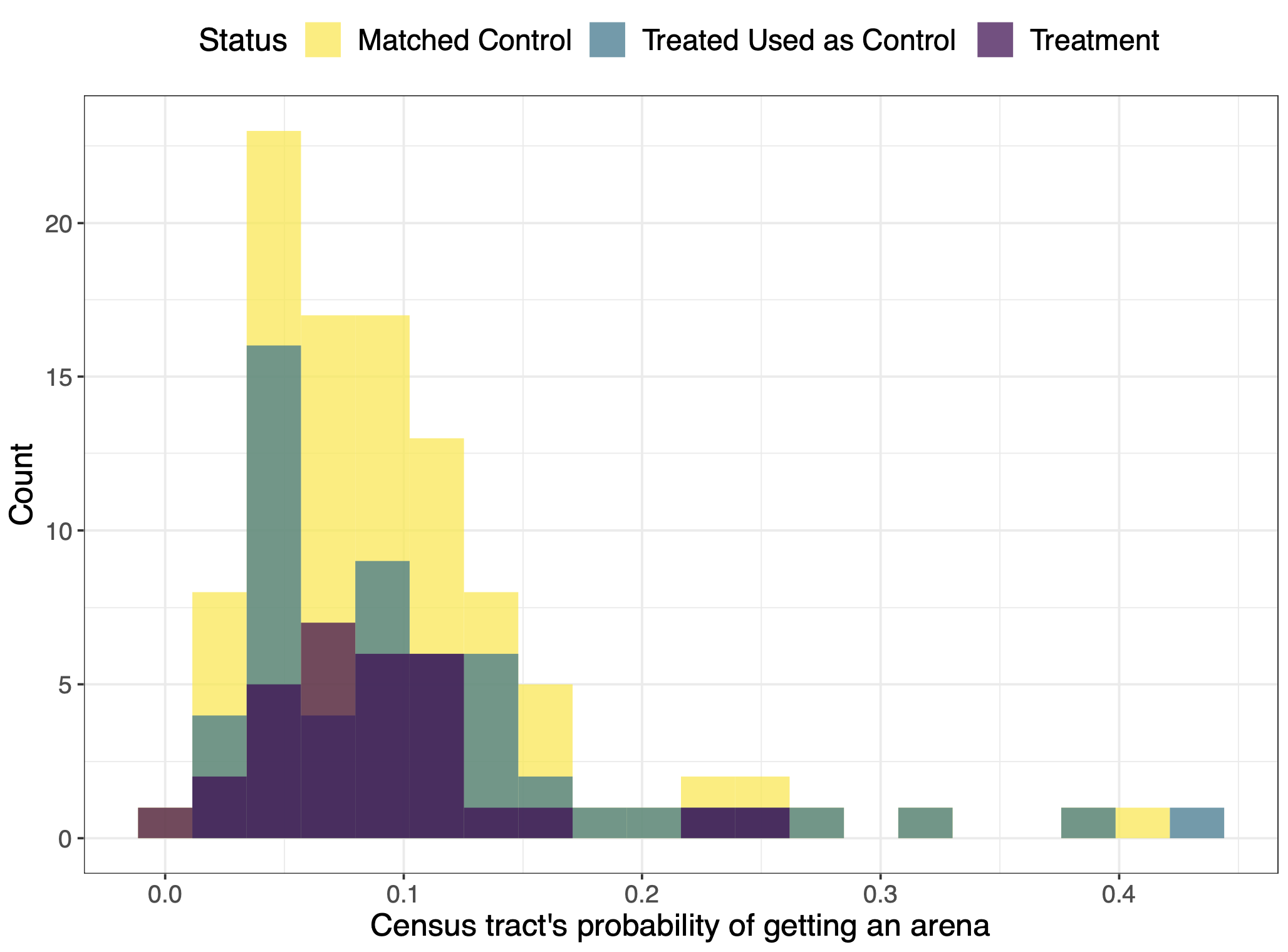

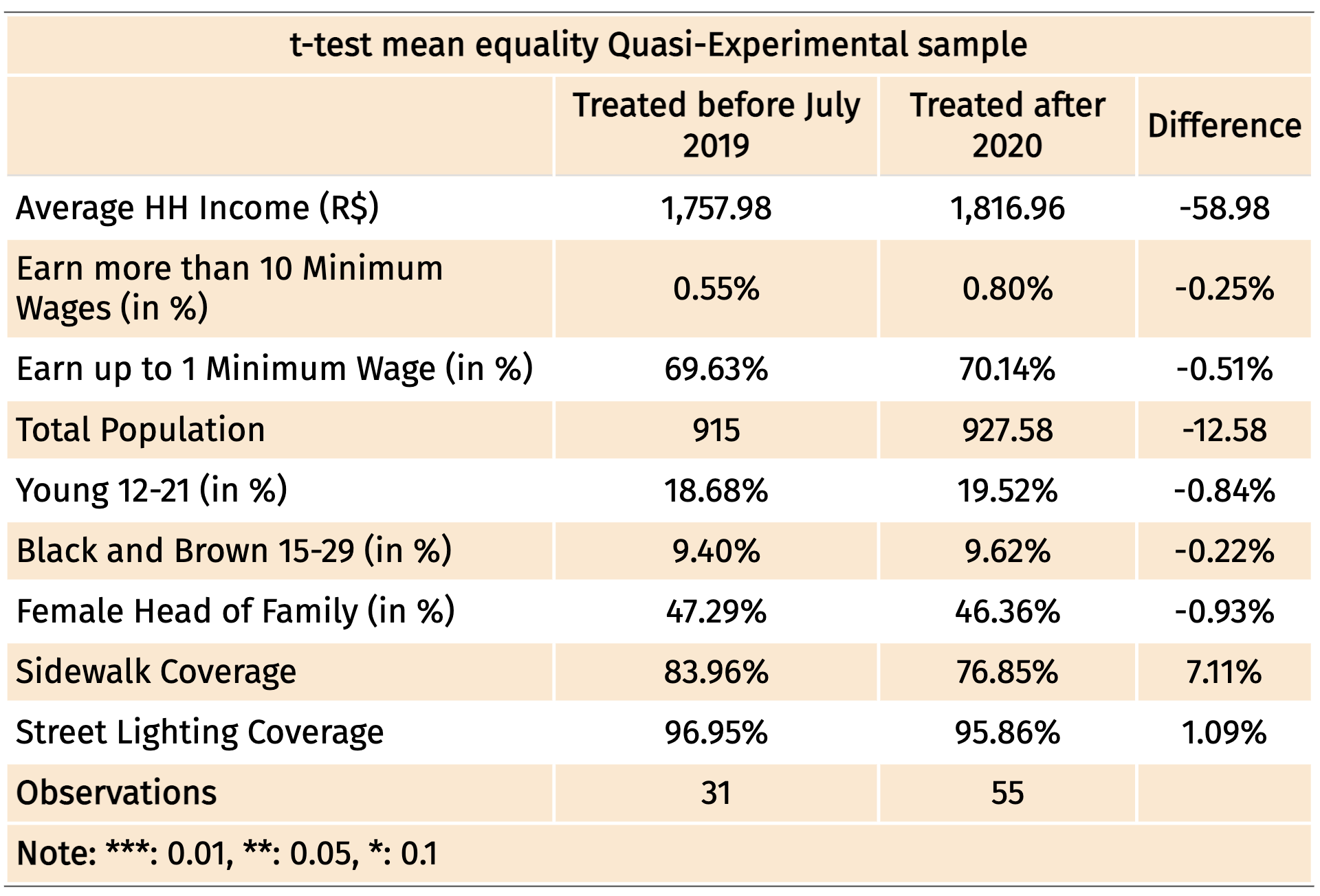

I conjecture tracts treated until July 2019 and after January 2020 are similar in observables and unobservables, and this control group’s choice produces an apples-to-apples comparison

Potential control areas within 650 meters of a treated neighborhood are excluded (2), as well as fields built between September and December 2019 (11)

Different comparison groups are also built by matching similar never treated neighborhoods using neighborhoods and boroughs’ demographics available in Census 2010

In total, there are 31 treated and 55 control neighborhoods

Total population in treated areas is 28,365 and in control tracts is 51,017

This sample covers 3.2% of the city’s population and around 6% of land area

To account for endogeneity concerns and evaluate the impact of the Areninhas Project, I combine the difference-in-differences design with a comparison group based on areas treated after the sample final year and/or matched places.

The causal effect of the neighborhood intervention is estimated using the following:

\[\text{Murder Rate}_{im}=\lambda_{m}+\gamma_{i}+\beta Open_{im}+\varepsilon_{im}\text{ } \text{ } \text{ }\text{ }\text{ } (1)\]

where \(\lambda_{m}\) is the time fixed effects (month-year), and \(\gamma_{i}\) refers to census tract fixed effects. \(\beta\) is the difference-in-differences estimate that captures the causal effect of interest

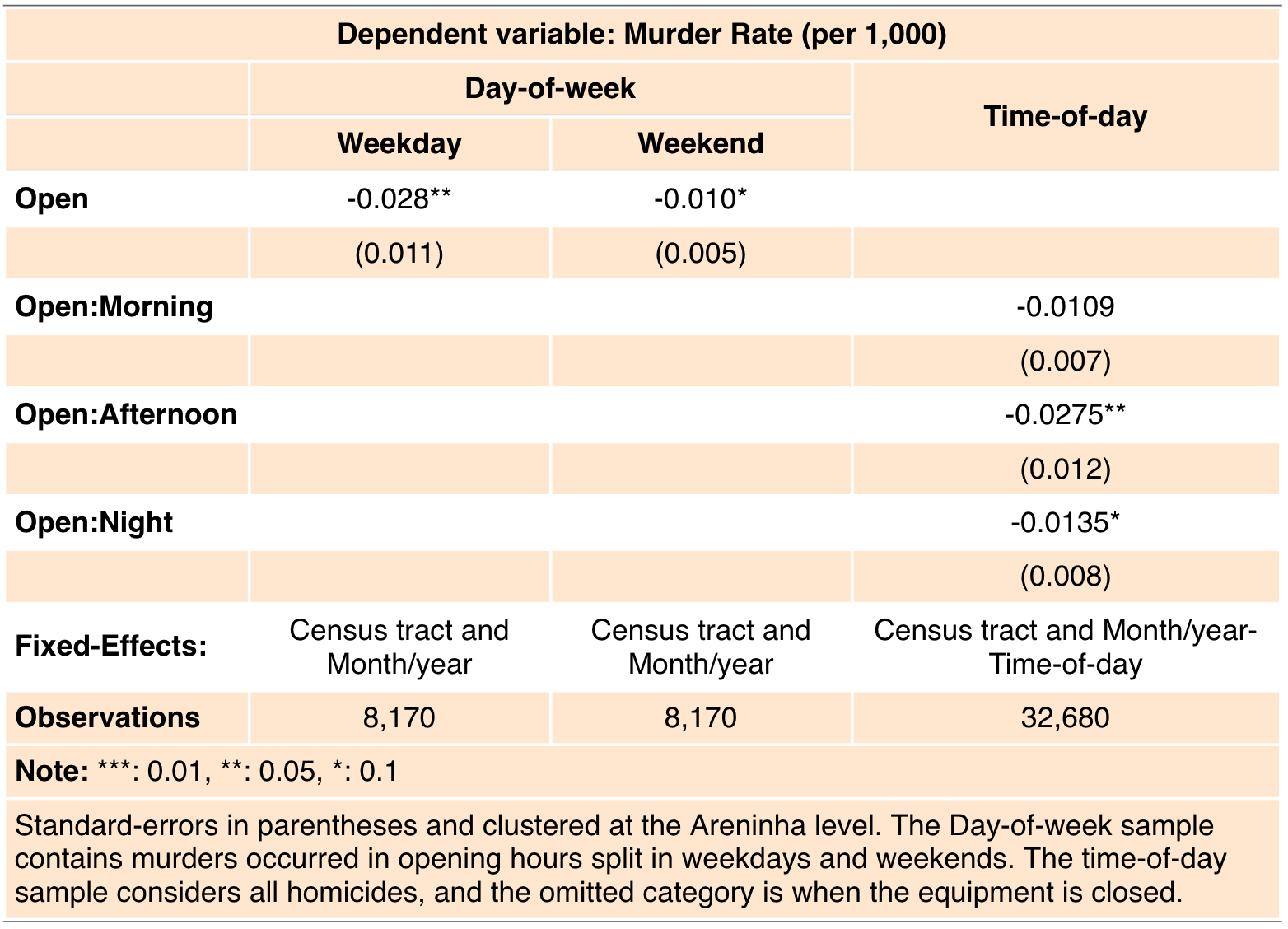

TWFE with Time-of-day heterogeneity

To check whether this urban intervention have different effects within hours of day, I consider the following:

\[\text{Murder Rate}_{iqt}=\lambda_{mt}+\gamma_{i} +\beta_{1}Open:Morning_{imt}+\beta_{2}Open:Afternoon_{imt}+\beta_{3}Open:Night_{imt}+\varepsilon_{imt}\text{ } \text{ } \text{ }\text{ }\text{ } (2)\]

where \(\lambda_{mt}\) represents month-year-time-of-day fixed effects. The morning covers the hours from 8 to 11:59 am, afternoon 12:00 pm until 5:59 pm, and night 6:00 pm to 9:59 pm. The omitted category is ‘closed,’ covering the hours from 10:00 pm to 7:59 am.

TWFE splitting the sample: Day-of-week, Age, Gender, and Criminal record heterogeneity

To estimate gender, day-of-week, age and criminal record-specific effects, I consider the following:

\[\text{Murder Rate}^{j}_{im}=\lambda_{m}+\gamma_{i}+\beta Open_{im}+\varepsilon_{im} \text{ } \text{ } \text{ }\text{ }\text{ }(3)\]

where \(\text{Murder Rate}^{j}_{im}\) is the outcome measured in tract \(i\) for deceased individuals of gender/of age/with criminal-record/at day-of-week \(j\) in month \(m\).

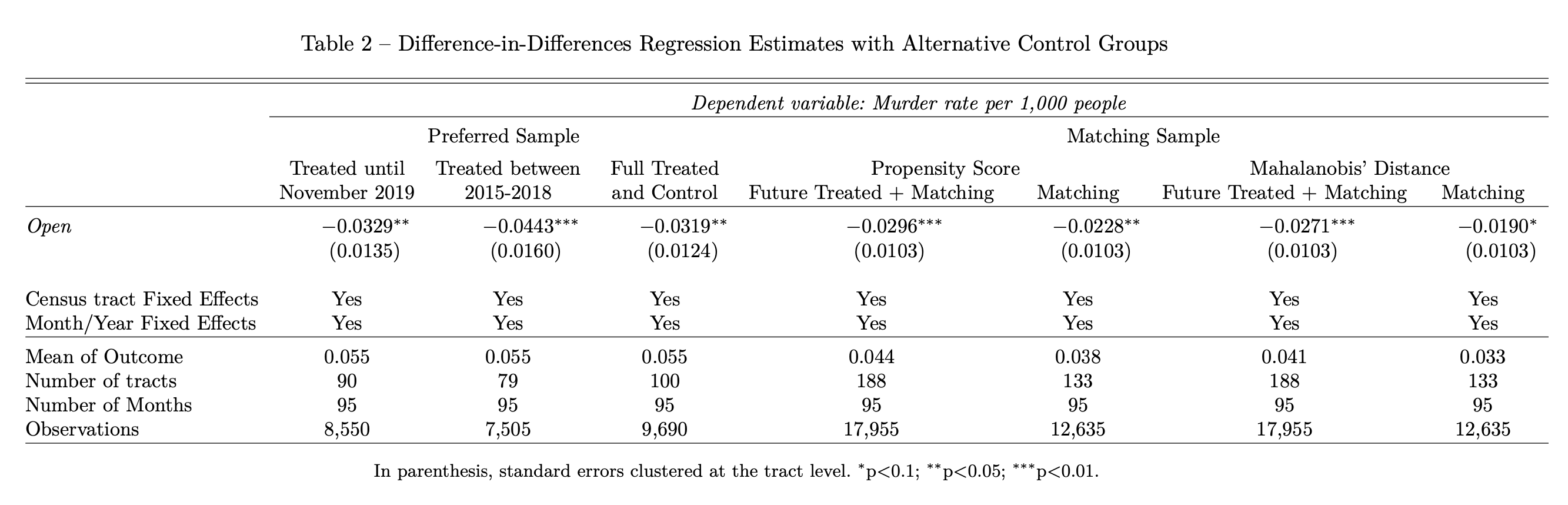

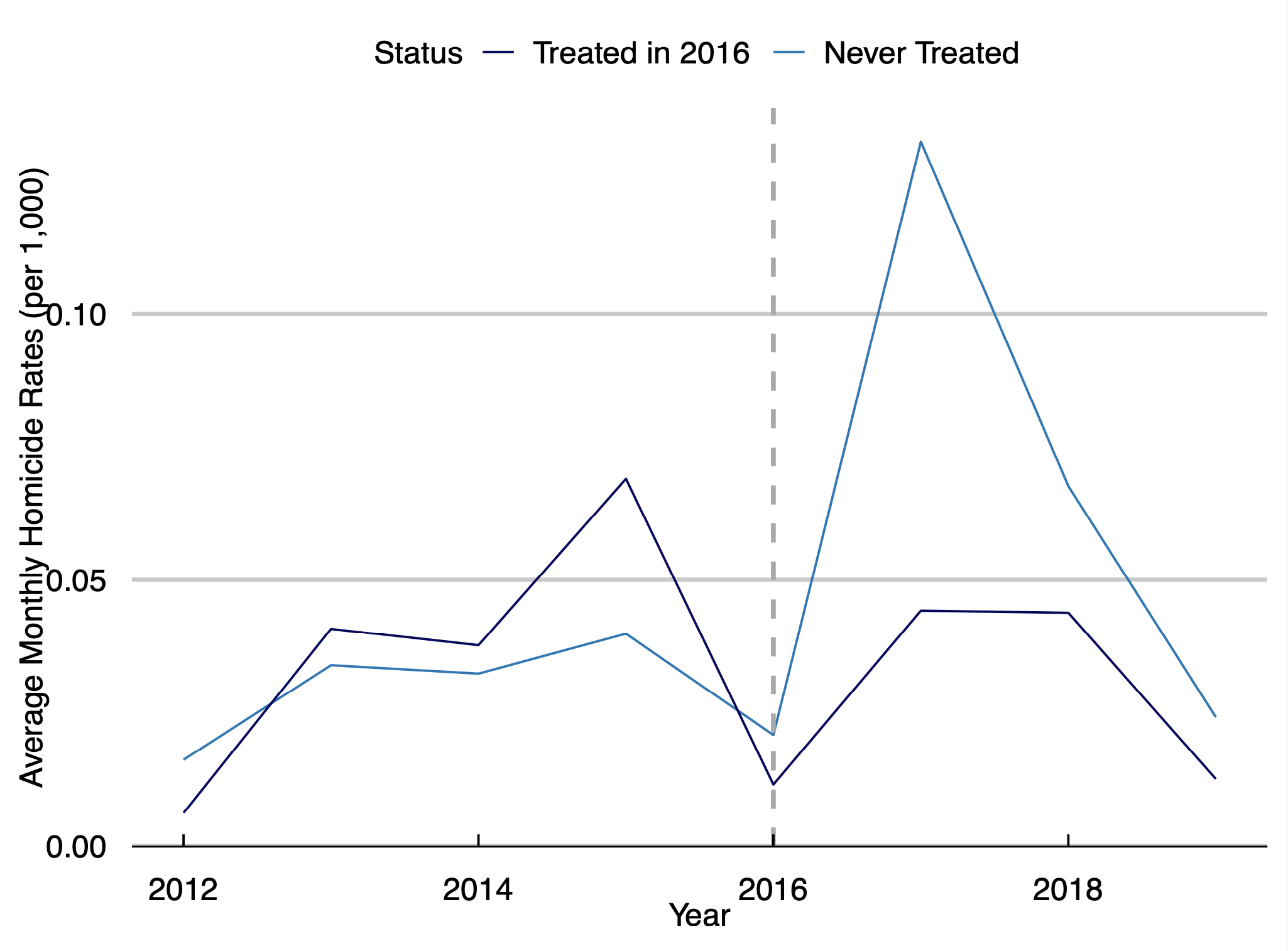

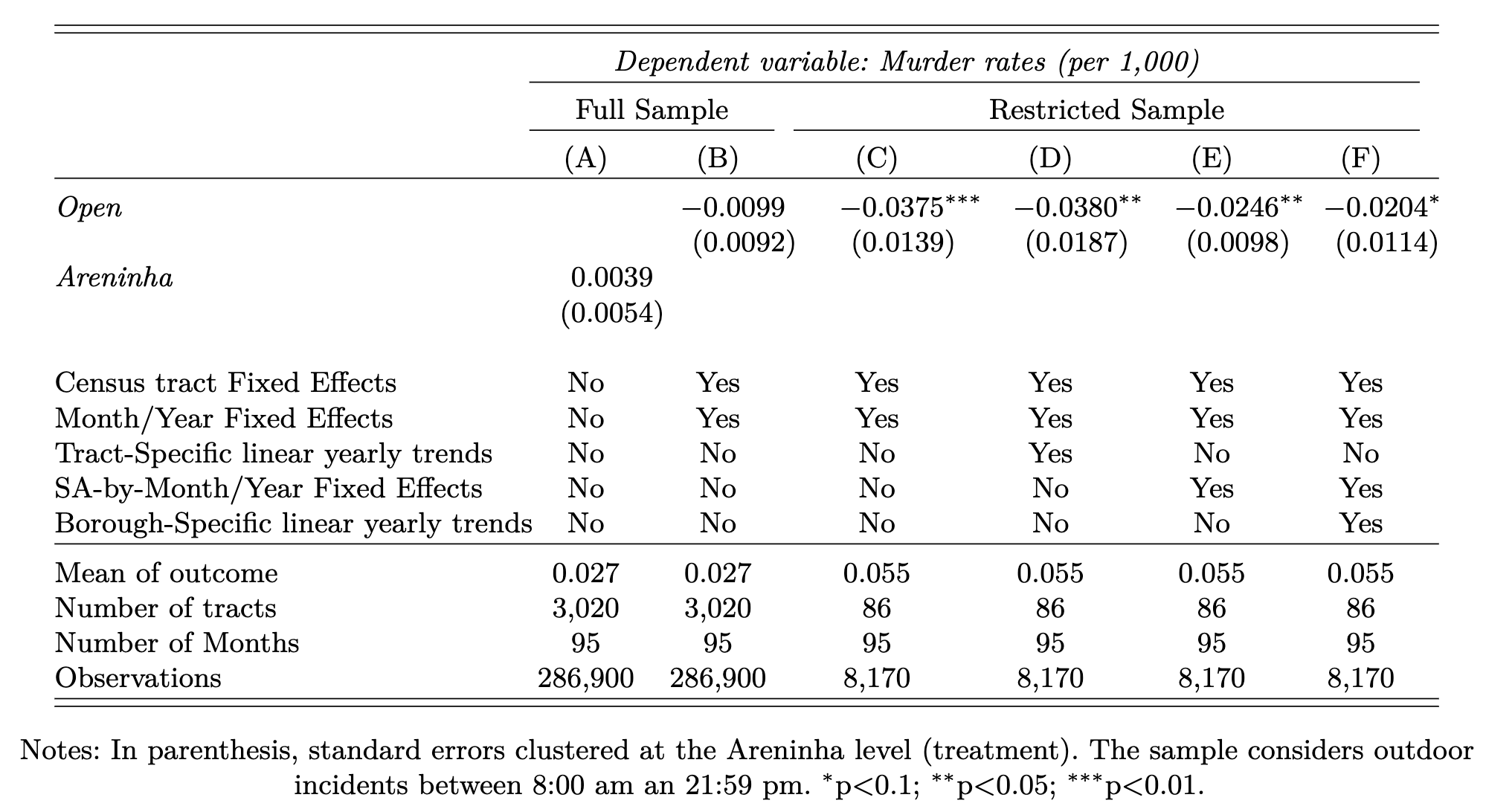

Results Crime I

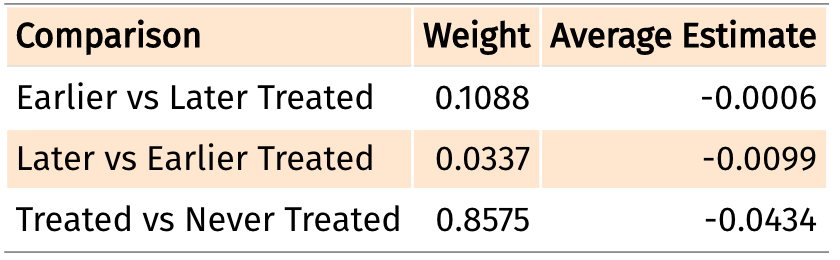

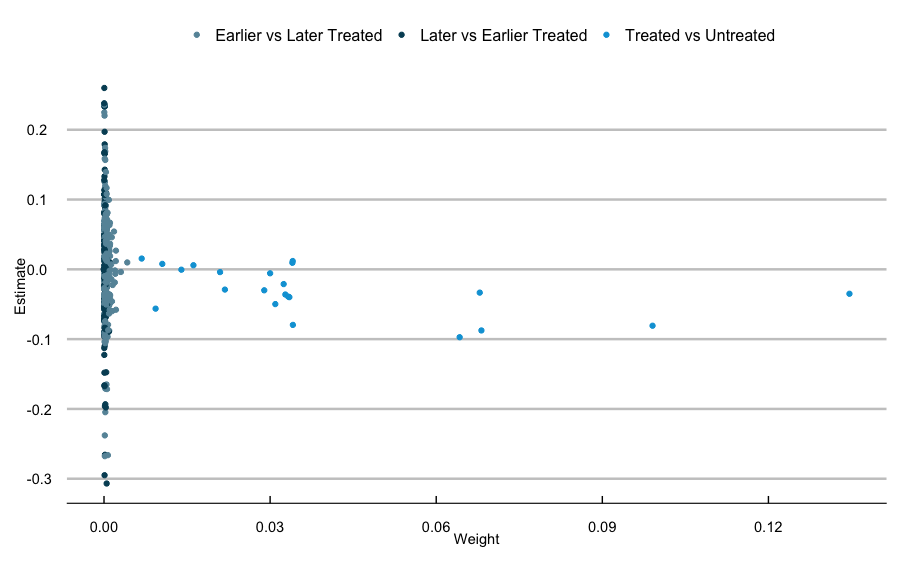

(A) shows a naive comparison of murder rates between treated census tracts and the rest of the city. (B) still uses full sample, but exploits the staggered rollout of the urban policy

(C) to (F) use the quasi-experimental sample. Results are statistically significant and meaningful: the urban renewal policy caused a decrease in murder rates around 45-68% in treated neighborhoods

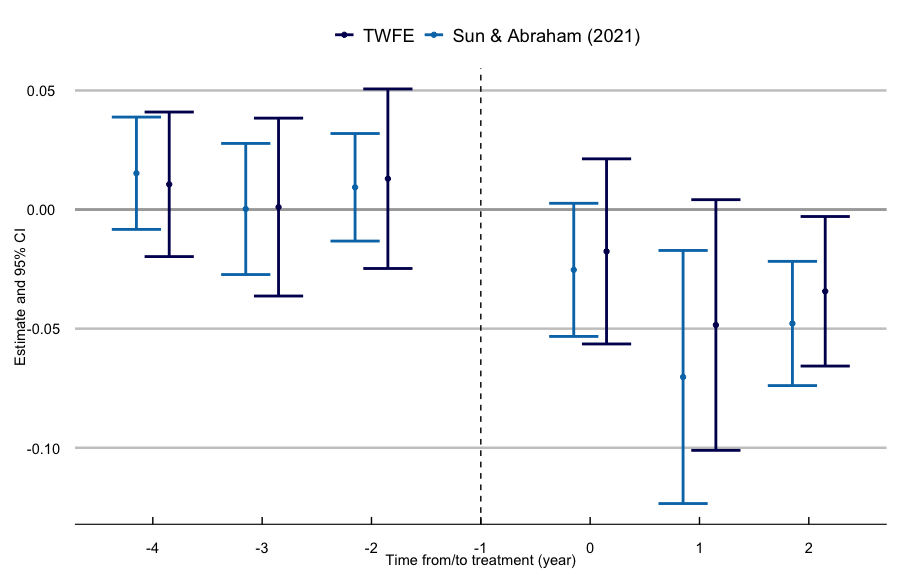

Dynamic treatment effects are estimated by

\[\small\text{Murder Rate}_{im}=\lambda_{m}+\gamma_{i}+\sum_{\tau=-4, \tau \neq -1}^{2}\beta_{\tau} Open_{i\tau}+\varepsilon_{im}\]

where months are binned to years, and endpoints are also binned at -4 (or less) and 2 (or more). Coefficients are normalized to event time -1

Day-of-week columns show a larger effect during weekdays, and time-of-day analysis points to a bigger effect during the afternoon (from 12 pm to 5:59 pm) - when most social projects happen

Pupils that study during the afternoon and commute from home to school around 1:00 pm and from school to home between 5:00-5:30 pm would benefit the most

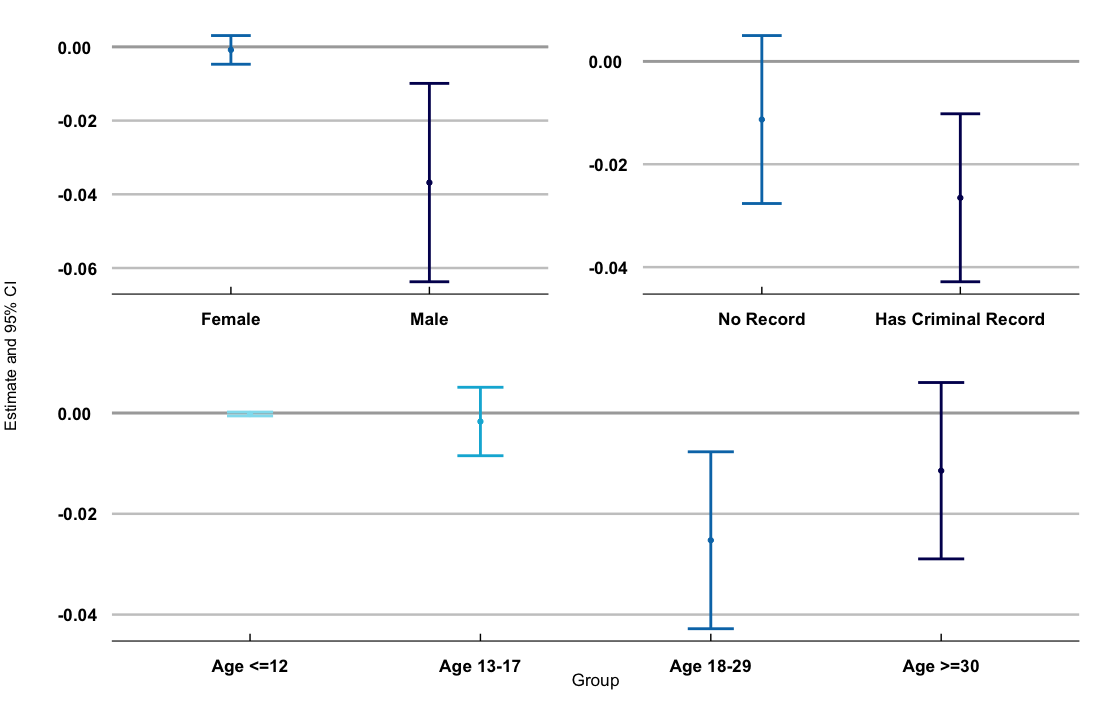

The effect is driven by males aged 18-29 with past criminal record, which suggests fewer gang fights in treated areas

Although there is anecdotal evidence of young males leaving the drug trafficking in these areas, incapacitation effect is hard to identify

Results Crime II

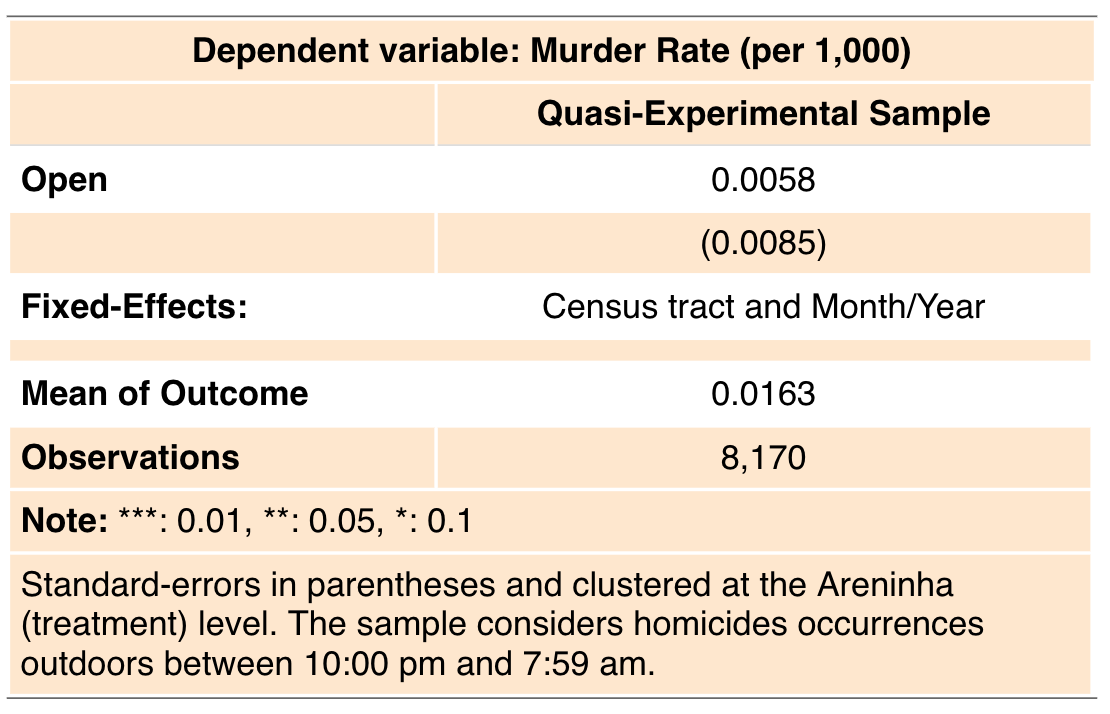

Temporal displacement is estimated using equation (1) but with murders happening during closed hours - from 22:00 pm to 7:59 am

Point estimate suggests an increase around 35% in homicide rates, but it is not statistically significant at usual levels (p-val=.49)

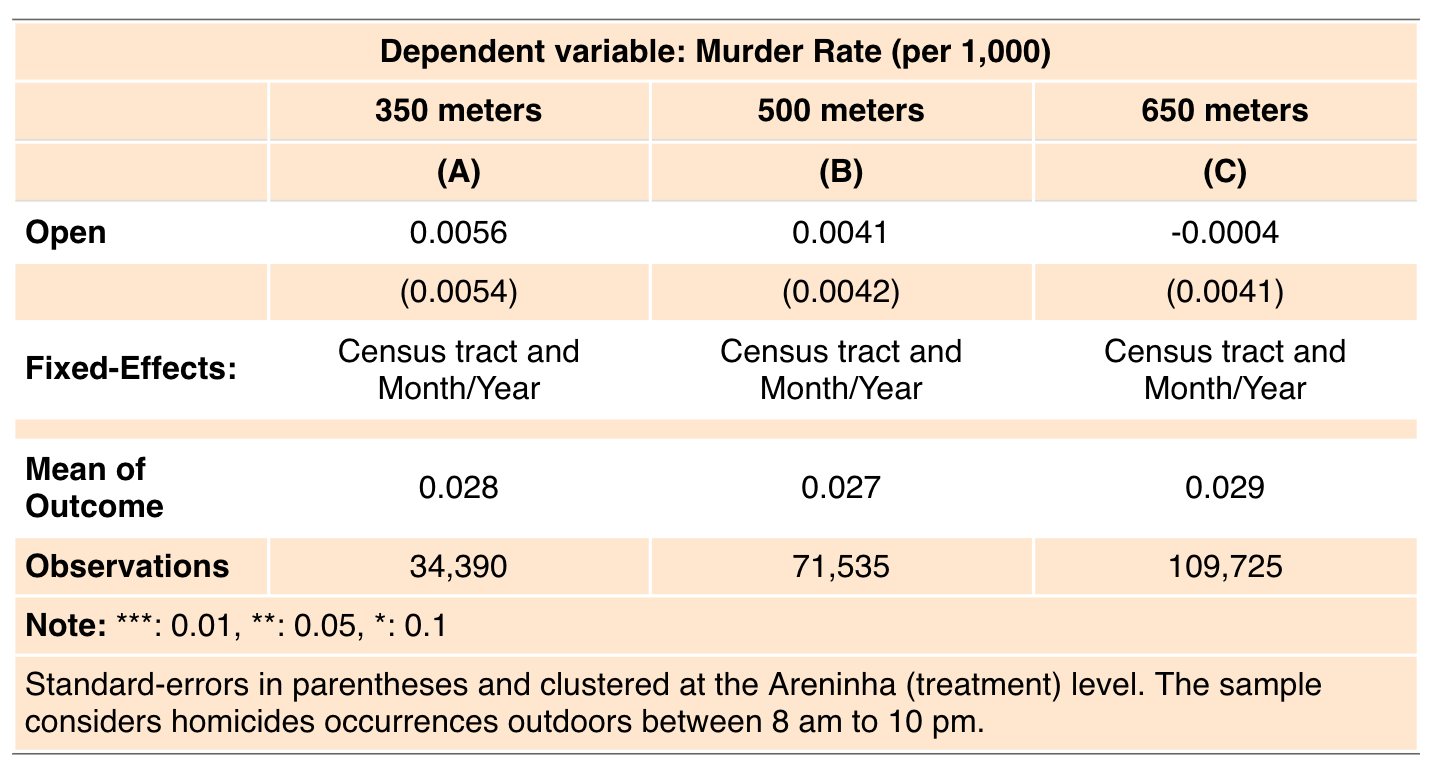

Neighborhoods are built around treated census tracts using the equipment’s distance to the other tracts’ centroids. The homicide data covers the opening hours

Point estimates are not statistically significant, and there is no evidence of crime moving around corners

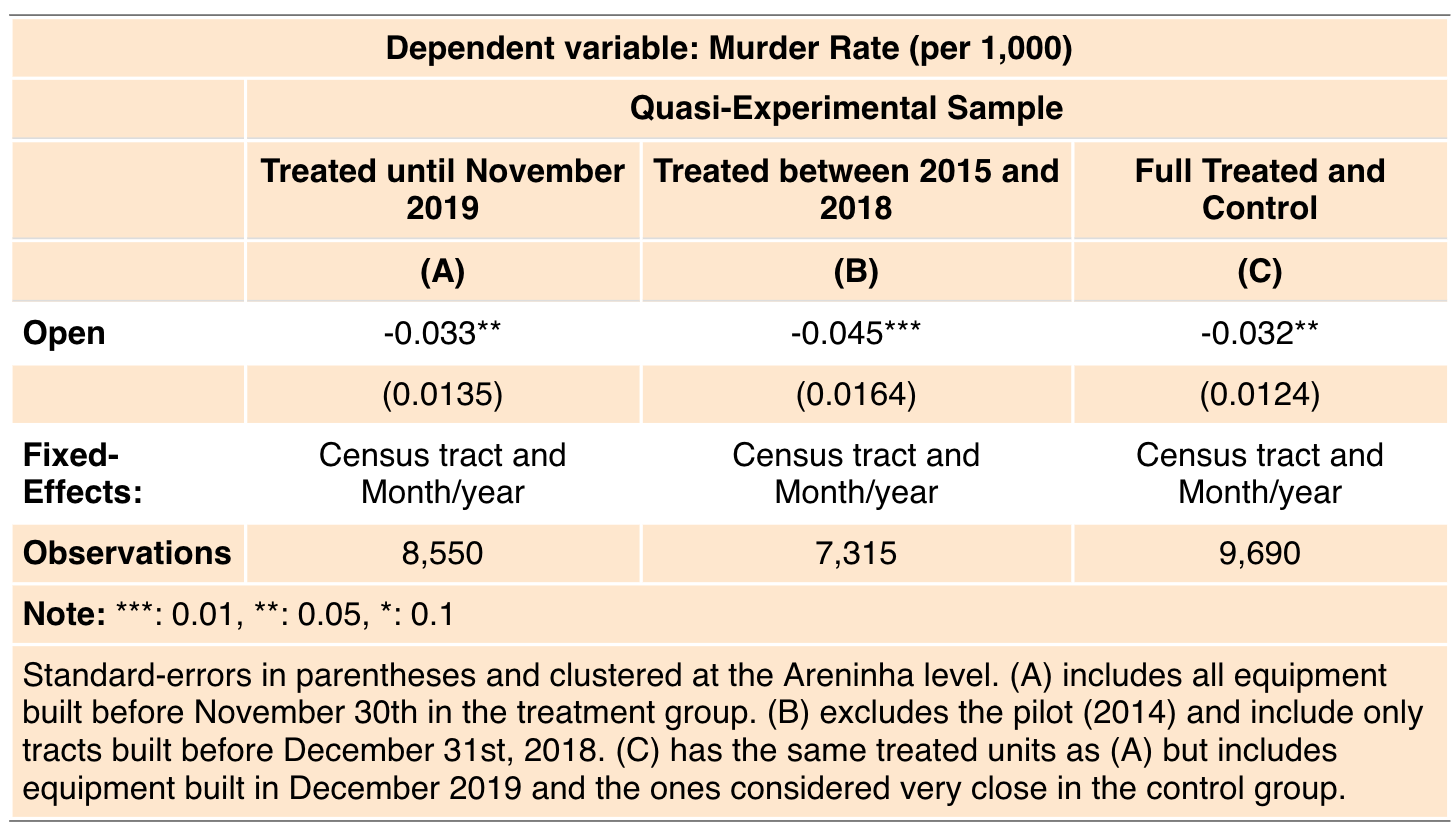

The table shows the results using different sample choices

Point estimates are similar to the ones using the preferred sample and show that results are not driven by neither treated areas at the begging nor the end of the program

Online Appendix contains results from different control group choices using matching. Results are fairly similar across different samples and point to average murder rates reductions between 57% and 67%

Cost-Benefit Analysis

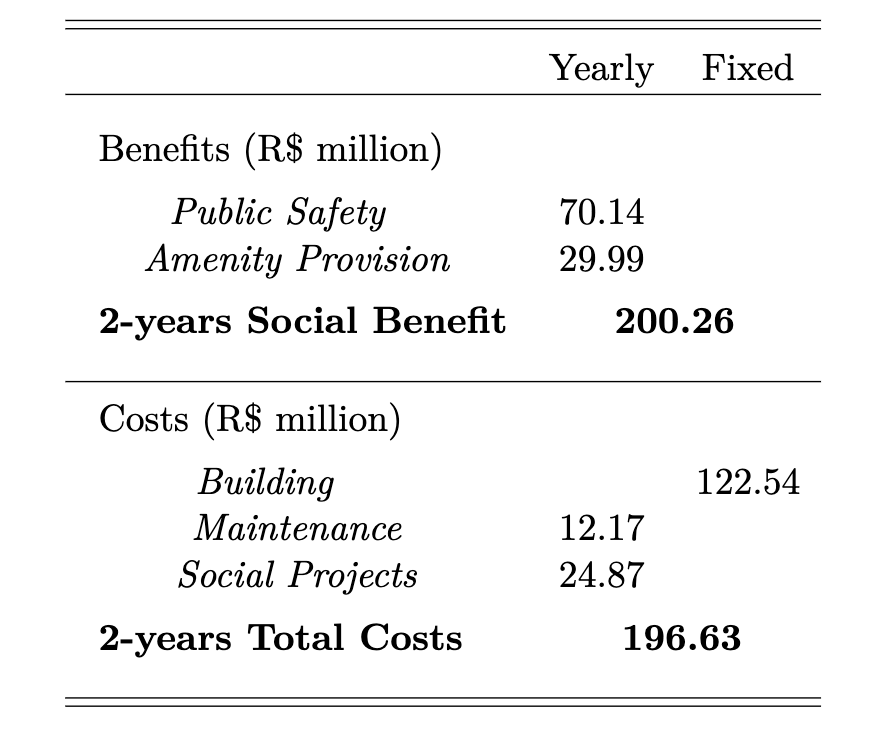

Back-of-envelop calculation shows that the 31 treated areas are having 18.86 fewer homicides every year. Extrapolating the effects to all 102 areas covered by 103 football fields, there are 62.68 fewer murders/year due to this policy. I follow Pereira, Almeida and Oliveira (2020), who attach R$ 1.119 million for a blue-collar Brazilian men

Amenity value is based on private turf field rentals at an hourly rate of R$ 100, considering 56 hours/week available for practice

Building costs vary from R$ .24 to R$ 1.7 million depending on the type of the equipment, and maintenance costs are composed by salaries, water and energy. There are four social projects connected to areninhas with an estimated cost of R$ 24.87 million/year

Takeaways

A blend of person- and place-based intervention might be a cost-effective strategy to reduce violent crimes and an alternative to policing

Successful interventions may cause diffusion of benefits to other areas such as school achievement

Place-based policies that involve the community or significantly change the neighborhood’s routine might have a greater impact on residents’ quality of life and prevent public goods from turning into public bads

Appendix

Less Policing, More Violence: Evidence from Police Strikes in Brazil

Motivation and Background

The Economics of Crime (Becker, 1968)

\[EU_{j}=p_{j}U_{j}(Y_{j}-f_{j})+(1-p_{j})U_{j}(Y_{j})\]

Common sense x Endogeneity

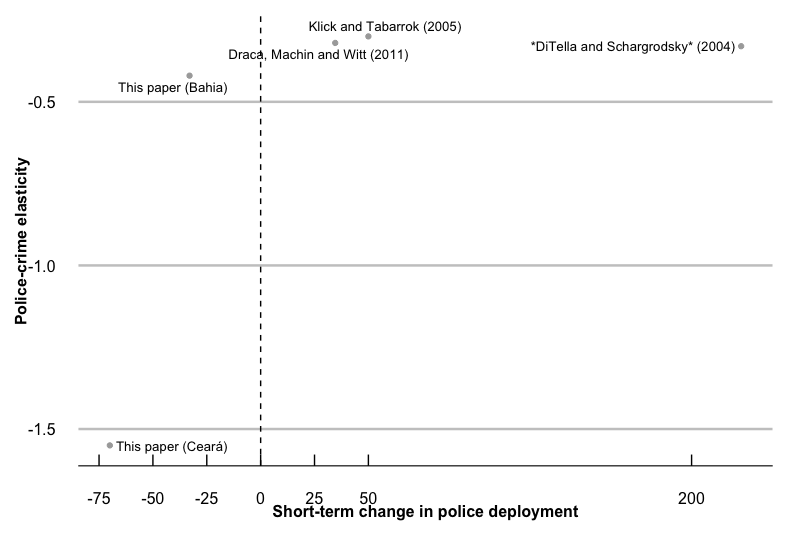

IV approach (Levitt, 1997; Mccrary, 2002; Levitt, 2002; Evans and Owens, 2007; Chalfin and Mccrary, 2018)

Difference-in-Differences (Di Tella and Schargrodsky, 2004; Klick and Tabarrok, 2005; Draca, Machin, and Witt, 2011; Mello, 2019)

Deterrence x Incapacitation

Effect of police strikes on public safety

Different Brazilian law enforcement categories walked off the job on more than 700 occasions between 1997 and 2020

During this period, the Military Police of almost all states went on strike 53 times

Contributions

- The causal effect of the absence of Police patrolling on violence

The deterrent effects of Police presence are large for murder and robbery

Motor vehicle theft x Motor vehicle robbery: criminals preferred violent methods when \(p_{j}\) was very low

In particular, the implications of Police strikes on public safety

- Significant changes in police deployment in large areas - 9 and 14 million people affected in Ceará and Bahia, respectively

- Two different natural experiments, very similar results

- Virtually no incapacitation effect

- Daily data fully identify the shock, treatment turns on and off

- It is possible to see belief updating during and after the strike

- Asymmetric effects of \(p_{j}\)

- Heterogeneous effects agree with the law of crime concentration

Sample Construction I

I focus on the Brazilian Northeast from 2011 to 2012. During this period, the Military Police went on a strike in six different states (mainly in the Northeast region). Sizable walkouts occurred in Maranhão (10 days), Ceará (6 days), and Bahia (12 days)

Northeastern states have similar socioeconomic and demographic levels, as well as violence patterns. Hence, I target states in that region for both control and treated groups

Among the Brazilian Northeast, Ceará, Alagoas, Sergipe, Bahia, Paraíba and Pernambuco divide their territory into Security Areas (SAs). They aim to improve police work by integrating the Fire department, Civil and Military Police

Sample Construction II

Data

Data consists of four categories of daily crime:

Violent and lethal crime against a person (murder)

Violent crime against property (robbery)

Theft

Sexual assault

To reduce measurement error, I use vehicle robbery and vehicle theft separately

Other states either do not divide their territory into SAs or could not provide meaningful information

Civil vs. Military Police

Two separate analyses - different duration and intensity of strikes

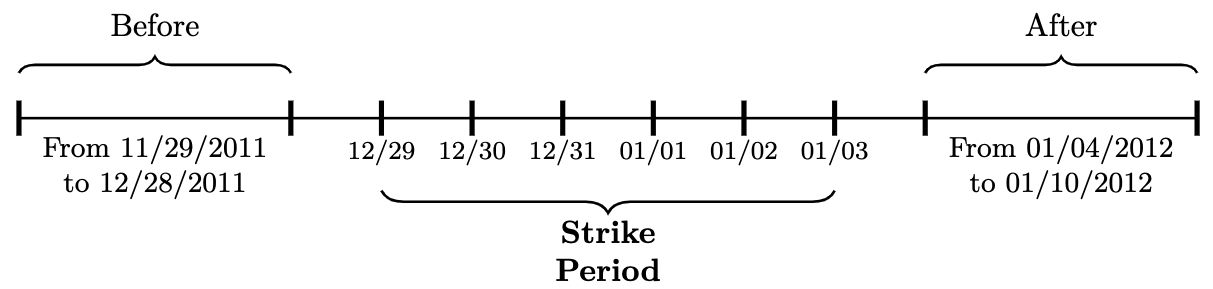

Time line of Events

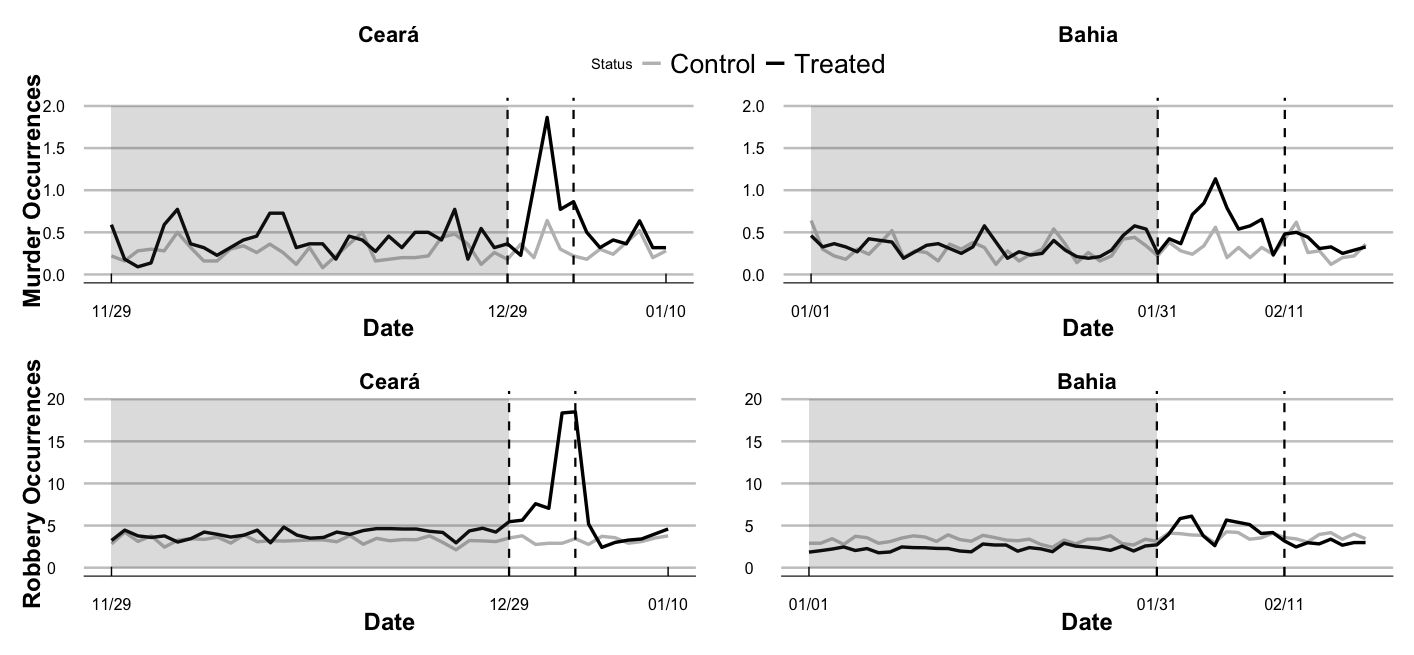

Crime information from November \(29^{th}\), 2011 to January \(10^{th}\), 2012

Comprehends 22 treated SAs (Ceará), and 50 SAs as control - 26 in Pernambuco, 24 in Alagoas

6 days of strike, around 70%-90% decrease in the number of Police officers on the streets

![]()

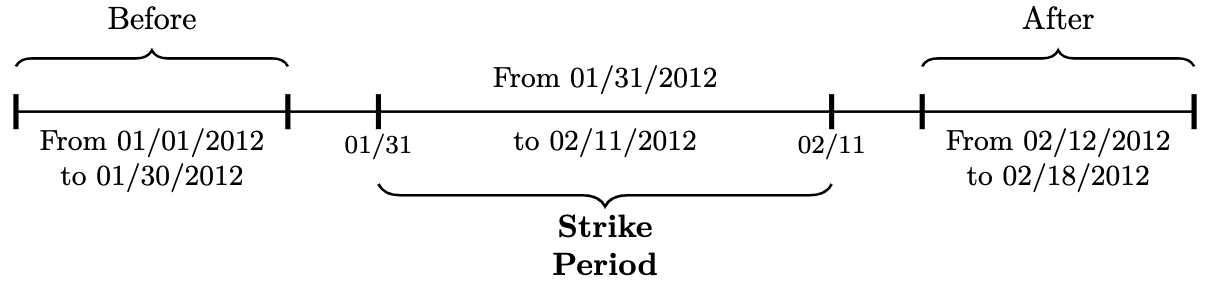

Crime information from January \(1^{st}\), 2012 to February \(18^{th}\), 2012

52 treated SAs in Bahia, and 50 SAs as control (Pernambuco and Alagoas)

12 days of strike, around 33%-50% decrease in the number of Police officers on the streets

![]()

Identification and Estimation I

Identification and Estimation II

Two-way fixed effects

\[Crime_{ist}=\lambda_{t}+\gamma_{i}+\beta Dint_{st}+\tau_{wd,i}+\varepsilon_{ist}\]

SA-by-day-of-week \((\tau_{wd,i})\) fixed effects to allow different SAs to follow different day of week trajectories

Treatment leads and lags to get a sense of the time dynamics

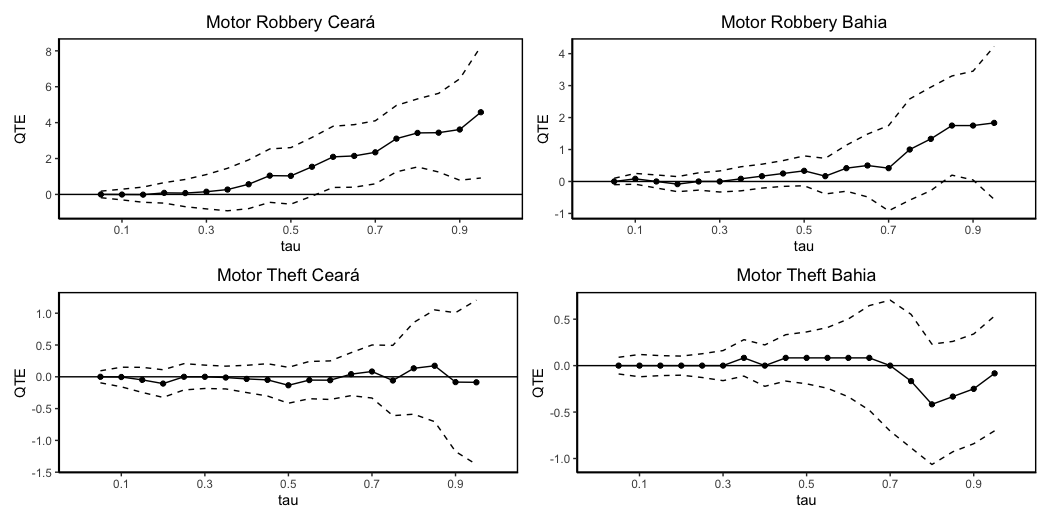

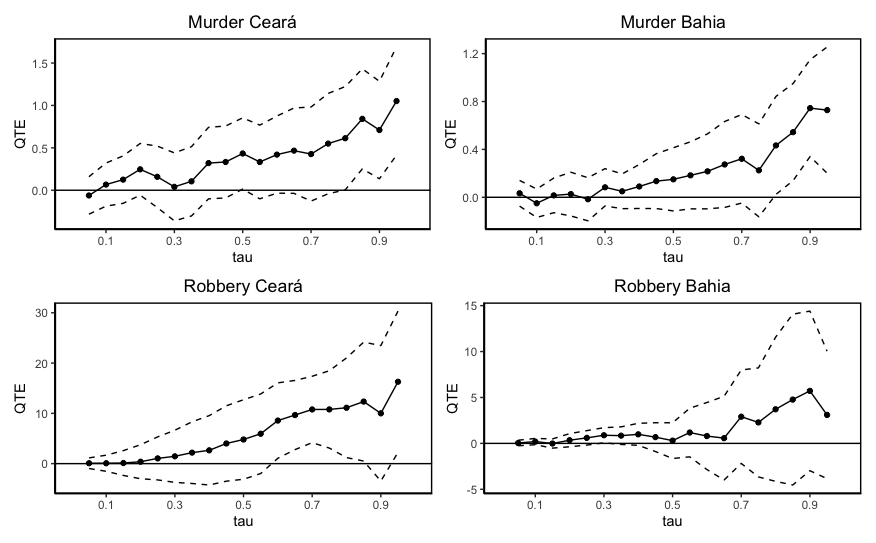

Quantile Difference-in-Differences (QDiD)

- QDiD allows treatment effect heterogeneity so one can understand the distributional impacts of the Police strike

Synthetic Difference-in-Differences (Arkhangelsky et al. 2021)

SDID generalizes DID and Synthetic Control (SC): the method re-weights and matches pre-exposure trends to weaken the reliance on common trends

SDID emphasizes units that on average are similar in terms of their past to the treated units and emphasizes periods that are on average comparable to the target periods

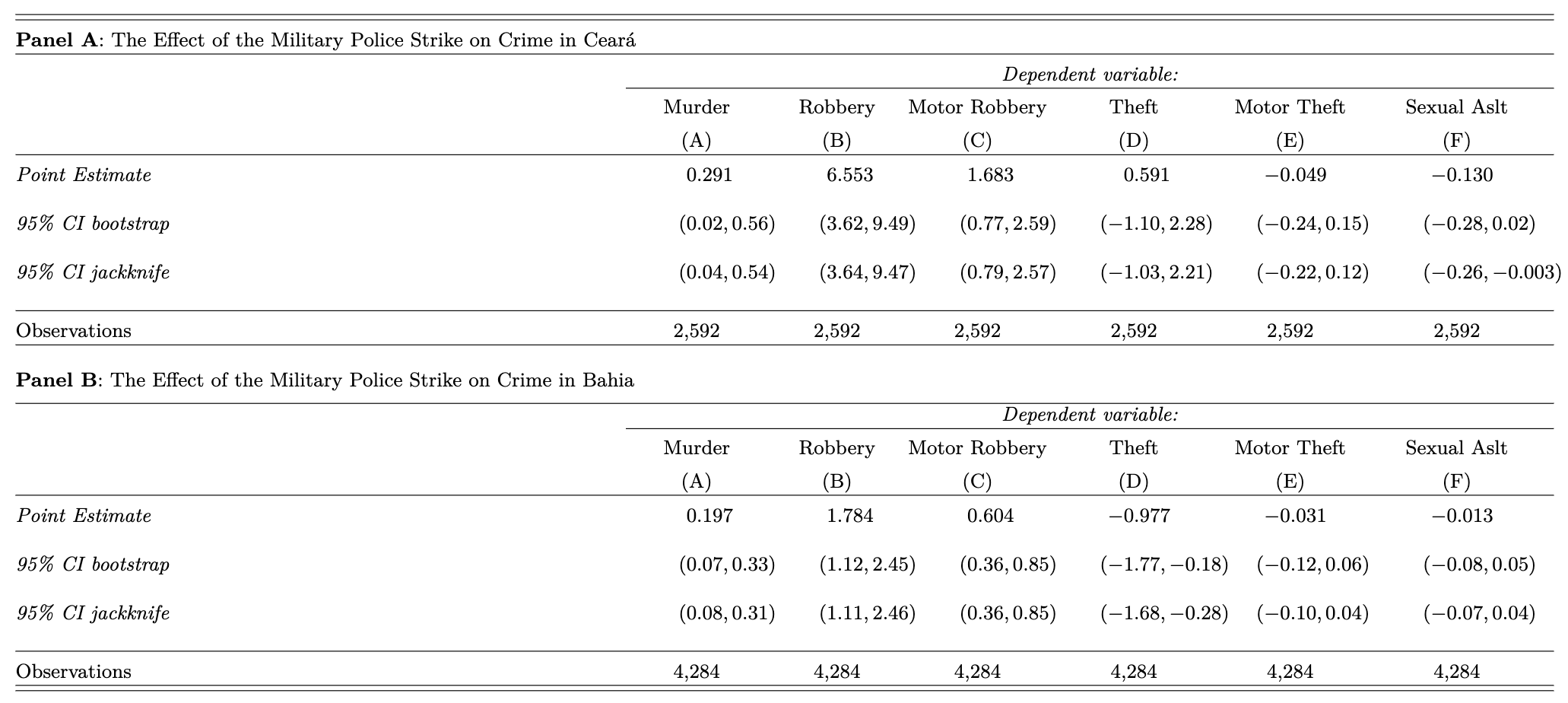

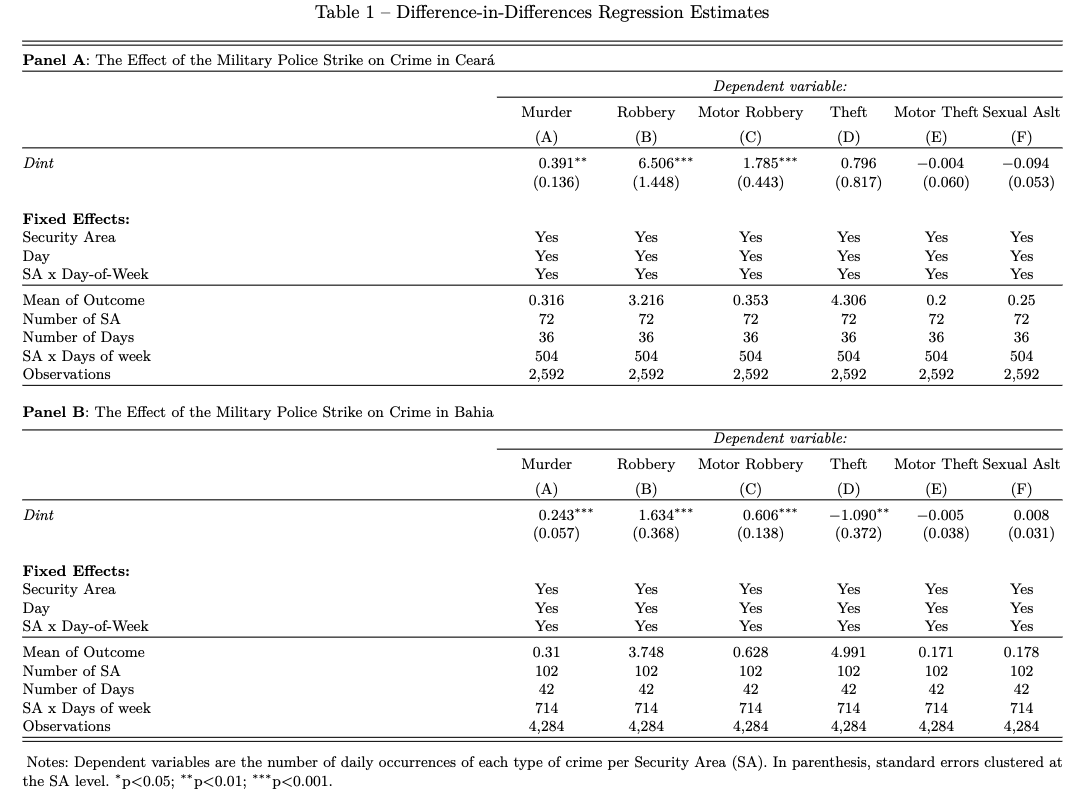

DiD Estimates

Murder increased by 123.7% and 78.38%, while robbery grew by 202.3% and 43.59% in Ceará and Bahia, respectively

There is no reaction of motor theft, but motor robbery increased 5-fold and 96.5% in Ceará and Bahia, respectively

Murder and robbery elasticities range from [-1.56, -1.37] and [-2.24,-0.87]

Event-studies

No other period repeats the inverted-U shape one see during Police strikes

Small reaction after the first two-three days

Violence return to regular levels after the ending of the strikes

QDiD Estimates

There are more cops allocated in the capital and metro area

Crime concentrates in few security areas

Treatment effects are much higher at upper percentiles

Takeaways

Violent crimes have a huge cost to society and this paper shows the essential role of deterrent effect on crime when police patrolling levels are low

- In particular, criminals switch to violent methods when \(p_{j}\) was very low

Time dynamics show perceived risk of arrest matched reality as time passed

Large elasticities associated to fewer cops suggest non-linear effects of police presence on crime

Appendix

Does Crime Relocate? Estimating the (Side)-Effects of Local Police Interventions on Violence

Motivation and Background

Based on Becker’s (1968) model, most of the crime economics literature focuses on the estimation of the “deterrent effect”

- e.g., Levitt (AER 1997,2002), Di Tella and Schargrodsky (AER 2004), Klick and Tabarrok (J. Law. Econ. 2005), Draca, Machin, and Witt (AER 2011), Chalfin and Mccrary (Restat 2018), among others

It is already painful to properly establish the causal effect of police on crime due to simultaneity, and displacement of criminal activities is often ignored

Those “more cops, less crime” studies have no words on what exactly extra cops do on the streets

This study seeks to evaluate one of the most common policing strategies in Brazil: the allocation of blitzes

Well defined place-based intervention with precise policing assignment

Large-scale intervention: 2004 blitzes over 2012

Spatio-temporal disaggregation allows the estimation of full displacement effects/diffusion of benefits

Data and Context

Police Blitzes

2004 identified blitzes in 450 census tracts over 52 weeks of 2012

Crime data

Violent crimes (homicide, robbery and bodily injury) at census tract level

Fortaleza’s socioeconomic profile (Census 2010)

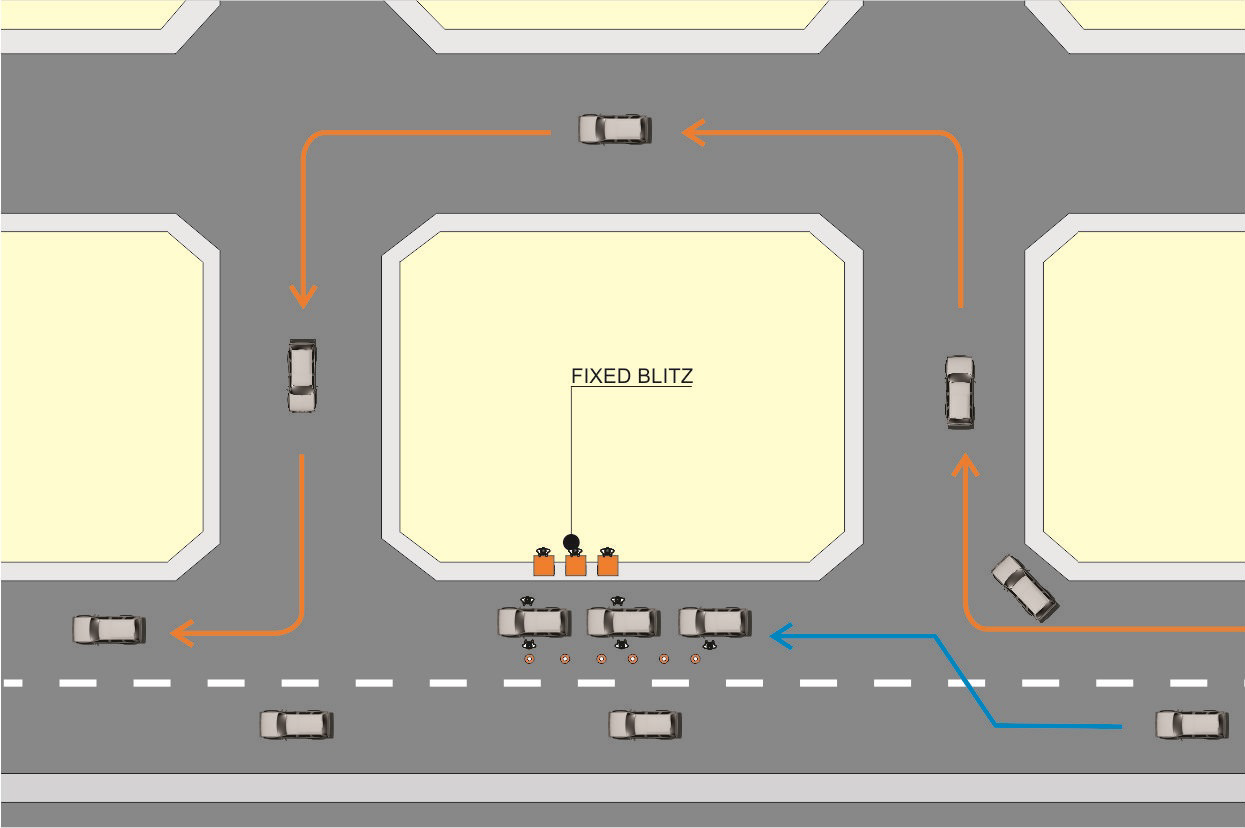

Allocation of Blitzes

A blitz interrupts the flow of vehicles and people through a physical, visual, and audible warning. Police officers proceed with checks and inspections in selected targets

This sudden increase in policing (5-10 policemen) in a street segment usually lasts between 3 and 6 hours

The Bureau of Police Operations met every Friday to decide where to allocate blitzes in the following week. That decision was mainly based on the past spatial distribution to create residual deterrence

Identification and Estimation

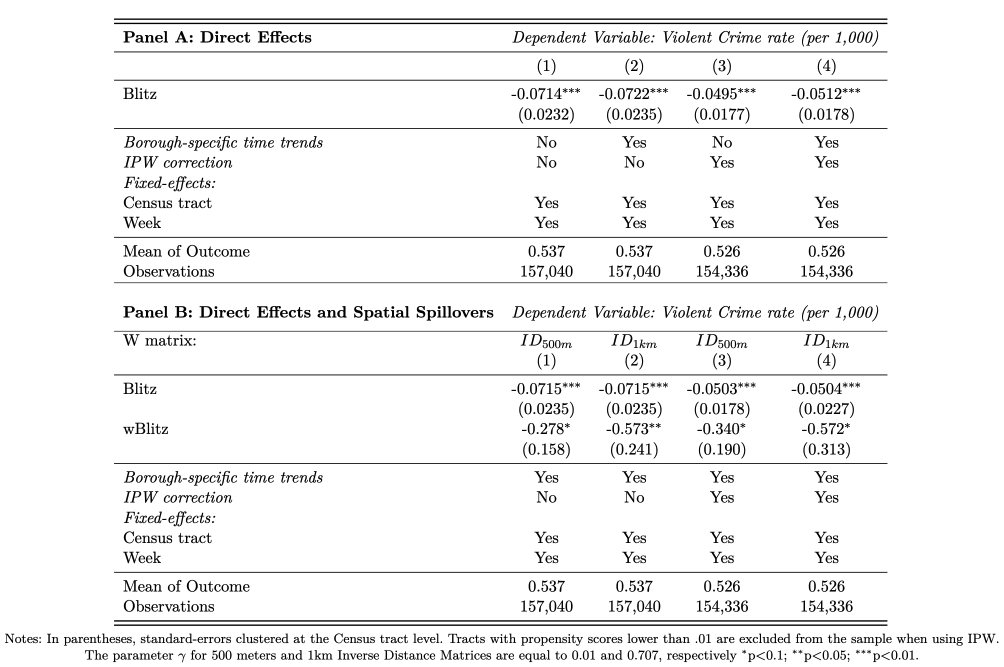

As mentioned before, it is challenging to disentangle the effect of police on crime. I deal with the simultaneity using police crackdowns that essentially tried to surprise drivers in space and time and do not depend on shocks to crime levels. The reduced-form model that captures the direct effect of the increase in policing on crime:

\[ \text{VCrimerate}_{it}=\delta Blitz_{it}+c_{i}+\lambda_{t}+\varepsilon_{it} \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } (1) \]

Conditional on time and census tracts fixed effects, the allocation of blitzes in a small area \((0.1 km^{2})\) at a given week is treated as good as random and used to identify the causal effect of local police interventions on crime. For robustness, borough-specific time trends are included and some specifications weight observations with inverse-propensity score (IPW)

The reduced-form model that captures the total effects of the increase in policing on crime (SLX model):

\[ \text{VCrimerate}_{it}=\delta Blitz_{it}+\theta WBlitz_{it}+c_{i}+\lambda_{t}+\varepsilon_{it} \text{ } \text{ } \text{ } (2) \]

- \(WBlitz_{it}\) is the weighted average of blitzes in the surrounding area of sector \(i\) at week \(t\)

The main neighborhood specification considers a parameterized spatial weight matrix \((W)\) that is based on the inverse distance of the blocks’ centroids. Distance cutoffs set the “areas of influence” of the police intervention

The weights of the \(W\) matrix are defined as \(w_{ij}=\cfrac{1}{d_{ij}^{\gamma}}\), where \(d_{ij}\) is the distance between census tracts \(i\) and \(j\) and \(\gamma\) is a distance decay parameter to be estimated

The estimated \(\gamma\) minimizes the SSR of the equation (2)

Results

Direct effects of local police interventions range from 9.41 to 13.3%. Indirect effects are around 2.61-5.82%

The interpretation of the \(wBlitz\) coefficient is not straightforward. One needs to take into account that it represents the average number of blitzes in the neighborhood at a certain cutoff

- Within 500m, an average census tract has 11.1 neighbors, and at 1km cutoff that number increases to 41.6.

Future Work

New dataset with precise location of 3,497 police interventions at street level. Each intervention is located within hexagons of 0.0178 \(km^{2}\) from January \(9^{th}\), 2012 to December \(15^{th}\), 2013

Knowing the exact time that each blitz starts and ends, we divide each

day between 2012/01/01 and 2013/12/20 into 48 30-minute intervals, which generates a time sequence with a length of 34,513There are 42,392 30-minute police interventions in the new dataset (21,196 hours), which is best to estimate residual deterrence