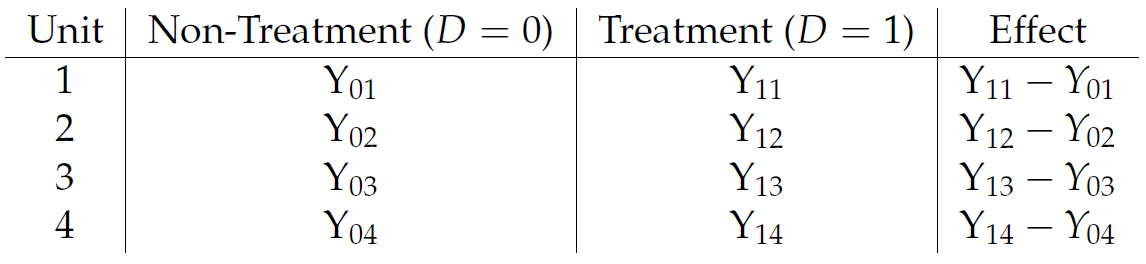

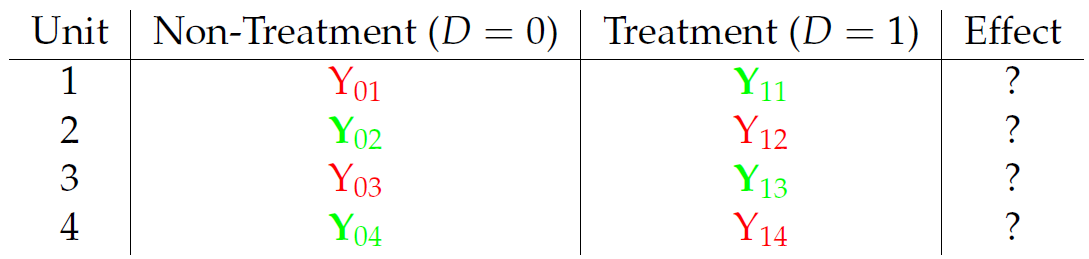

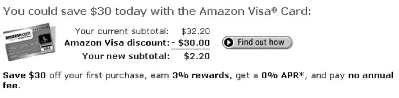

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Econ 474 - Econometrics of Policy Evaluation ## The Experimental Ideal ### Marcelino Guerra ### January 24-26, 2022 --- <style type="text/css"> .pull-left3 { float: left; width: 65%; } .pull-right3 { float: right; width: 32%; } .pull-right3 ~ p { clear: both; } </style> # Example: Health Insurance .pull-left[ * The Affordable Care Act (ACA) required Americans to buy health insurance. The idea behind that is the government-mandated health insurance might yield a health dividend * Many people who are not covered by Medicare/Medicaid decide to not participate in an employer-provided insurance plan and rely on hospital emergency departments when they need * The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) provides detailed information on health/health insurance, asking questions like "Would you say your health, in general, is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?" * **Does the survey provide evidence about the effect of health insurance on health status?** ] .pull-right[ <table class="table table-striped table-condensed" style="font-size: 14px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="empty-cells: hide;border-bottom:hidden;" colspan="1"></th> <th style="border-bottom:hidden;padding-bottom:0; padding-left:3px;padding-right:3px;text-align: center; " colspan="3"><div style="border-bottom: 1px solid #ddd; padding-bottom: 5px; ">Husbands</div></th> <th style="border-bottom:hidden;padding-bottom:0; padding-left:3px;padding-right:3px;text-align: center; " colspan="3"><div style="border-bottom: 1px solid #ddd; padding-bottom: 5px; ">Wives</div></th> </tr> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Some HI </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> No HI </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Difference </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Some HI </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> No HI </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Difference </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr grouplength="1"><td colspan="7" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Health</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Health Index </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.98 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.70 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 0.278 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.99 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.61 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 0.382 </td> </tr> <tr grouplength="7"><td colspan="7" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Other Characteristics</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Nonwhite </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.20 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.19 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 0.011 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.20 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.18 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 0.018 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Age </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 44.16 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 41.27 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 2.893 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 42.15 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 39.52 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 2.631 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Years of Education </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 14.13 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 11.21 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 2.919 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 14.27 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 11.36 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 2.913 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Family Size </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.55 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 4.06 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> -0.506 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.55 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 4.07 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> -0.520 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Employed </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.92 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.85 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 0.070 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.76 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.54 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 0.216 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Family Income </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 104002.44 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 43636.02 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 60366.415 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 103363.63 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 43641.39 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> 59722.242 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Sample Size </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 7866.00 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1529.00 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 7950.00 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1445.00 </td> <td style="text-align:left;font-weight: bold;"> NA </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> .small[**Note: This table reports average characteristics for insured and uninsured married couples in the 2009 NHIS. Columns 2, 3, 5, and 6 show average characteristics of the group of individuals specified by the column heading. Columns 4 and 7 report the difference between the average characteristic for individuals with and without health insurance (HI)**] ] --- class: inverse, middle, center # Rubin Causal Model --- # Potential Outcomes (*a priori*) .pull-left[ * To better describe the problem, think about the insurance status as a dummy variable `\(D_{i}\)` that takes on the values 0 and 1. The outcome of interest - a measure of health condition - is denoted by `\(Y_{i}\)` * The question is whether health insurance (**the treatment variable**) affects health condition (**the outcome**). To answer it, we can imagine what would have happened to someone who had health insurance had that person never being insured. Hence, for any individual, there are two potential states of the world: .bg-washed-yellow.b--orange.ba.bw2.br3.shadow-5.ph4.mt1[ `\begin{equation*} \text{Potential Outcome}= \begin{cases}Y_{1i} & \text{if } D_{i}=1 \\ Y_{0i} & \text{if }D_{i}=0 \end{cases} \end{equation*}` ] ] .pull-right[ * `\(Y_{i0}\)` is the health status had individual `\(i\)` never being insured, and `\(Y_{i1}\)` is the individual's health condition if insured * Ideally, we would like to calculate the difference between `\(Y_{i1}\)` and `\(Y_{i0}\)` to get the causal effect (treatment effect) of having insurance on health condition for individual `\(i\)`  ] --- # Observed Outcomes (*a posteriori*) .pull-left[ .center[**Unfortunately, we cannot travel in time and change a person's treatment status**  ] ] .pull-right[ **The fundamental problem of causal inference** is that we cannot observe units in both counterfactual states. Hence, it is impossible to observe the treatment effect on a particular unit In reality, the data look like this:  Some individuals are treated; others are not. What we can do is to observe multiple subjects and learn about the average effects of health insurance by comparing the health status of those who are and are not covered ] --- # The Selection Problem * The **observed outcome**, `\(Y_{i}\)`, can be written in terms of potential outcomes as `\begin{equation*} Y_{i}= \begin{cases}Y_{1i} & \text{if } D_{i}=1 \\ Y_{0i} & \text{if }D_{i}=0 \end{cases} \end{equation*}` * In other terms, `\(Y_{i}=D_{i}Y_{1i}+(1-D_{i})Y_{0i}\)` * Naive comparisons of averages by insurance status tell us something about potential outcomes, but not exactly what we are looking for. The comparison of average health conditional on coverage status is formally expressed by: .bg-washed-yellow.b--orange.ba.bw2.br3.shadow-5.ph4.mt1[ `\begin{equation*} \underbrace{E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=0]}_{\text{Observed difference in average health}}= \underbrace{E[Y_{1i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]}_{\text{Average treatment effect on the treated}}+\underbrace{E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=0]}_{\text{Selection bias}} \end{equation*}` ] --- # The Selection Problem * The term `\(E[Y_{1i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]=E[Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]\)` represents the average causal effect of health insurance on those who had coverage, i.e., the difference between the health of the insured, `\(E[Y_{1i}|D_{i}=1]\)`, and what would have happen to them had they not been covered, `\(E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]\)` * The observed difference in health status adds to the causal effect the term we call selection bias, i.e., the difference in average `\(Y_{0i}\)` between the insured and the uninsured: `\(E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=0]\)`. `\(Y_{0i}\)` is shorthand for everything about person `\(i\)` related to health other than insurance status (years of education and family income, for instance) * Thus, we cannot recover the causal effect of interest comparing the average outcomes of the two groups. Even without treatment, the average outcomes might be different from the start, and health status comparisons between the insured and the uninsured are not apples-to-apples * Note that we know those two groups differ in some observed characteristics. If the only source of selection bias is a set of differences in characteristics that we observe and measure, that problem is relatively easy to fix. The main challenge is the elimination of the selection bias that comes from unobserved differences --- class: inverse, middle, center # Randomized Trials --- # The Law of Large Numbers .panelset[ .panel[.panel-name[LLN] .pull-left[ * The LLN characterizes the behavior of sample averages relative to sample sizes. In particular, the LLN states that a sample average can be brought as close as possible to the average in the population from which it is drawn simply by enlarging the sample size * Let's play fair dice! The numbers 1 to 6 are equally likely to appear, and we expect to see each value an equal number of times if we play long enough. Hence, the expected outcome is an equally-weighted average of each possibility: `$$\dfrac{1+2+3+4+5+6}{6}=3.5$$` ] .pull-right[  ] .panel[.panel-name[R code] ```r #### Generating 500 samples dice_roller<-lapply(1:500, function(x) sample(1:6, size=x, replace=TRUE )) #### Getting the averages of these samples means<-as.data.frame(sapply(dice_roller, mean)) names(means)[1]<-"Average" means$`Number of Trials`<-1:500 ## Set the working directory to export the .gif setwd("C:/Users/User/Desktop") ## Generating the .gif packages<-c("tidyverse", "ggplot2", "ggthemes", "gganimate") lapply(packages, library, character.only = TRUE) dice_rolls<-means %>% ggplot( aes(x=`Number of Trials`, y=Average)) + geom_line(size=1.4, color="skyblue4")+ geom_hline(yintercept=3.5, color="darkorange", size=1.6)+ theme_economist(base_size = 14)+ scale_colour_economist()+ scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq(from = 1, to =6 , by =.5))+ theme(axis.text=element_text(size=12),axis.title=element_text(size=12,face="bold"))+ transition_reveal(`Number of Trials`) animate(dice_rolls, renderer=gifski_renderer("dice.gif")) ``` ] ] ] --- # Randomization Solves Selection Bias * When the sample at hand is large enough - so the LLN works -, random assignment of treatment `\(D_{i}\)` solves the selection problem because randomization makes `\(D_{i}\)` independent of potential outcomes .bg-washed-yellow.b--orange.ba.bw2.br3.shadow-5.ph4.mt1[ `\begin{equation*} E[Y_{i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{i}|D_{i}=0]=E[Y_{1i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=0]=E[Y_{1i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1] \end{equation*}` ] * The independence of `\(Y_{0i}\)` and `\(D_{i}\)` makes `\(E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=0]=E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]=E[Y_{0i}]\)` * Giving the random assignment, the expression can be further simplified to `$$E[Y_{1i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|D_{i}=0]=\underbrace{E[Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}|D_{i}=1]}_{\text{Average treatment effect on the treated}}=\underbrace{E[Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}]}_{\text{Average treatment effect}}$$` * Although randomized trials are not problem-free, they solve the most important issue that arises in empirical research --- class: inverse, middle, center # RAND Health Insurance Experiment --- # RAND HIE * From 1974 to 1982, the RAND Health Insurance Experiment followed 3,958 people aged 14 to 61 from six areas of the country * RAND investigators wanted to know whether and by how much health-care use falls when the price of health care goes up * They also wanted to know whether more generous health insurance coverage causes better health * Participants were randomly assigned to one of 14 insurance plans that had a variety of provisions related to cost-sharing * We do the analysis grouping subjects who were assigned to similar HIE plans together * Families in the free care faced a price of zero * Coinsurance cuts prices to 25% or 50% of costs incurred * Families in the deductible and catastrophic coverage paid something close to the sticker price for care (up to the spending cap) --- # RAND HIE: Checking for Balance .pull-left[ .center[ **Do subjects randomly assigned to health insurance schemes look similar?** ] * The table presents demographic characteristics and health variables (pre-treatment outcomes) before the experiment * Differently from the NHIS survey, comparisons between distinct insurance coverage show that we are indeed comparing apples to apples * Small differences across groups most likely reflect chance variation that naturally emerges from the sampling process ] .pull-right[ <table class="table table-striped table-condensed" style="font-size: 14px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr><th style="border-bottom:hidden;padding-bottom:0; padding-left:3px;padding-right:3px;text-align: center; " colspan="5"><div style="border-bottom: 1px solid #ddd; padding-bottom: 5px; ">Plan Group Means</div></th></tr> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Catastrophic </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Deductible </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Coinsurance </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Free </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr grouplength="6"><td colspan="5" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Demographic Characteristics</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Female </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.560 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.537 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.535 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.522 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Nonwhite </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.172 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.153 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.145 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.144 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Age </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 32.4 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 32.9 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 33.3 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 32.8 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Education </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 12.1 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 11.9 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 12.0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 11.8 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Family Income </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 31603 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 29499 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 32573 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 30627 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Hospitalized last year </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.115 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.120 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.113 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.116 </td> </tr> <tr grouplength="5"><td colspan="5" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Baseline Health Variables</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> General Health Index </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 70.9 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 69.4 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 71.1 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 69.6 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Cholesterol (mg/dl) </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 207 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 206 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 205 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 202 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 122 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 125 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 123 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 123 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Mental Health Index </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 73.8 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 73.7 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 75.0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 74.7 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Number enrolled </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 759 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 881 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1022 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1295 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] --- # RAND HIE: Experiment Results .pull-left[ * The table shows results from the RAND HIE. One important finding was that subjects assigned to more generous plans used substantially more health care services * **Just as economists predict, the demand for a good goes up when it gets cheaper** * Since participants who didn't have to worry about health care costs enjoyed it more, one important follow-up question is: did the extra care make them healthier? * To answer that question, one can compare those averages related to health care variables and calculate **the average treatment effect** of health insurance plans ] .pull-right[ <table class="table table-striped table-condensed" style="font-size: 13px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr><th style="border-bottom:hidden;padding-bottom:0; padding-left:3px;padding-right:3px;text-align: center; " colspan="6"><div style="border-bottom: 1px solid #ddd; padding-bottom: 5px; ">Plan Group Means</div></th></tr> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Catastrophic </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Deductible </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Coinsurance </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Free </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> Any Insurance </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr grouplength="5"><td colspan="6" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Health Care Use</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Face-to-face visits </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 2.78 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 2.98 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.27 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 4.45 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3.68 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Outpatient expenses </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 248 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 290 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 308 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 417 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 348 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Hospital admissions </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.0991 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.1150 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.1014 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.1279 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0.1158 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Inpatient expenses </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 388 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 460 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 480 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 504 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 485 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Total expenses </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 636 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 750 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 788 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 921 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 834 </td> </tr> <tr grouplength="5"><td colspan="6" style="border-bottom: 1px solid;"><strong>Health Outcome</strong></td></tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> General health index </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 68.5 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 67.6 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 69.1 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 67.7 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 68.1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Cholesterol (mg/dl) </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 203 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 204 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 201 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 201 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 202 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 122 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 123 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 120 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 121 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 122 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Mental health index </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 75.5 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 76.0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 76.6 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 75.9 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 76.1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;padding-left: 2em;" indentlevel="1"> Number enrolled </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 759 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 881 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1022 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1295 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 3198 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] --- class: inverse, middle, center # More on RCT --- # Regression Analysis of Experiments I Regression is a useful tool to analyze causal questions. With constant treatment effects, one can rewrite `\(Y_{i}=D_{i}Y_{1i}+(1-D_{i})Y_{0i}\)` as: `\begin{equation*} Y_{i}= \underbrace{\alpha}_{E(Y_{0i})} + \underbrace{\rho}_{(Y_{1i}-Y_{0i})} D_{i} + \underbrace{\eta_{i}}_{Y_{0i-E(Y_{0i})}} \end{equation*}` where `\(\eta_{i}\)` is the random part of `\(Y_{0i}\)`. Evaluating the conditional expectation of this expression according to treatment status: `$$E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=1]=\alpha+\rho+E[\eta_{i}|D_{i}=1] \text{ } (1)$$` `$$E[Y_{i} | D_{i}=0]=\alpha+E[\eta_{i}|D_{i}=0] \text{ } (2)$$` `\((1) - (2)\)` gives: `\begin{equation*} E[Y_{i}|D_{i}=1]-E[Y_{i}|D_{i}=0] = \underbrace{\rho}_{\text{Treatment Effect}} + \underbrace{E[\eta_{i}|D_{i}=1]-E[\eta_{i}|D_{i}=0]}_{\text{Selection Bias}} \end{equation*}` Thus, selection bias amounts to correlation between the regression term, `\(\eta_{i}\)`, and the regressor, `\(D_{i}\)`. --- # Regression Analysis of Experiments II In the regression framework, we can use covariates `\(X_{i}\)` as controls: `\begin{equation*} Y_{i}=\alpha+\rho D_{i}+X_{i}^{'}\gamma + \eta_{i} \end{equation*}` * If these controls are uncorrelated with the treatment `\(D_{i}\)`, then they will not affect the estimates of `\(\rho\)` * In other words, estimates of `\(\rho\)` in the (long) regression above will be very similar to estimates of `\(\rho\)` in the short regression `\(Y_{i}=\alpha+\rho D_{i}+ \eta_{i}\)` * The inclusion of covariates `\(X_{i}\)` may generate more precise estimates: although `\(X_{i}\)` and `\(D_{i}\)` are not correlated, control variables might have some explanatory power for `\(Y_{i}\)`. Hence, the inclusion of covariates reduces the residual variance, which in turn lowers the standard errors of the regression estimates * **You should only control for pre-assignment variables** --- # Internal and External Validity .pull-left[ ### Internal Validity * The extent to which the study truly establishes cause-and-effect relationships * The primary threat to the internal validity of experiments is SUTVA violations. Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA) rules out interference: the treatment applied to one individual does not affect the outcome of another subject * What about spillover effects? Crime displacement, contagion * Frequently, the solution is to redefine the unit of analysis (e.g., classes instead of students) ] .pull-right[ ### External Validity * The extent to which the conclusions of a study can be generalized * RCTs are performed under controlled conditions that might not be easily applied in other settings * This is addressed at the initial stages of research * In Economics, identification is important, but how much can we learn without theory? (not exclusive problem of RCTs) ] --- class: inverse, middle, center # A/B testing in practice --- # Introduction .pull-left3[ * A/B testing is a framework to evaluate different ideas about how to improve business * New Ideas `\(\rightarrow\)` Run Experiment `\(\rightarrow\)` Statistically Analyze Results `\(\rightarrow\)` Updating to "Winning Idea" * Usually, sustained progress is a matter of continued experimentation and many small improvements. **Sometimes, there are large surprising effects** * In 2012, an employee working on Bing suggested changing how *ad headlines* display. The idea was to lengthen the title line of ads by combining it with the text from the first line below the tile (as shown in the figure) * It was simple to code this change and to evaluate the idea on real users - i.e., to randomly show some users the new title layout (treatment) and others the old one (control) * Bing's revenue increased by 12% (over $100M annually in the US alone) ] .pull-right3[  .small[**Source:** Kohavi, Tang, and Xu (2020)] ] --- # Ingredients for A/B testing .pull-left[ 1. Experimental units There are users that can be assigned to different variants with **no interference** (SUTVA violations/internal validity) 2. Sample size There are enough users - the larger the number, the smaller the effects that can be detected. In that sense, another big question is how long to run the experiment? Be aware of seasonality, day-of-week effect, and primacy/novelty effects 3. Metrics There are key metrics that can be practically evaluated (conversion rates, clicks, revenue). You need to have information about your metrics before anything changes ] .pull-right[ In general, you want to test changes that are easy to make and evaluate. For instance, you might want to answer a question such as "Which button color generates more clicks?" (your outcome is clicks). Your current color is gray, but you think blue will do better. Based on your belief, you set up a hypothesis: using a blue color will result in more clicks. The treatment status is treated if blue, control if gray. ] --- # Examples from Google and Amazon .pull-left[ **Making an offer at the right time** In 2004, Amazon placed a credit-card offer on the home page. The team decided to ran an experiment moving the offer to the shopping cart page, showing simple math highlighting the potential savings  **Source:** Kohavi, Tang, and Xu (2020) ] .pull-right[  **Source: [@LuizCent](https://twitter.com/luizcent).** ] --- # Experimental Design and Power Analysis .pull-left[ 1. Statistical test you plan to run 2. Current value for the control condition 3. Expected value for the test condition 4. Proportion of the data from the test condition (usually 50/50) 5. Significance level `\((\alpha=0.05)\)` 6. Power `\((\text{Power}=1-\beta\text{, usually 0.8})\)` Power is the probability of rejecting the null when the null is false. In simple terms, power is the strength of your test to detect an actual difference between A and B (to detect `\(H_{a}\)`). Running a power analysis, you estimate the sample size needed to detect an effect of particular magnitude. To run a power analysis, we use the <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 581 512" style="height:1em;width:1.13em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:steelblue;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M581 226.6C581 119.1 450.9 32 290.5 32S0 119.1 0 226.6C0 322.4 103.3 402 239.4 418.1V480h99.1v-61.5c24.3-2.7 47.6-7.4 69.4-13.9L448 480h112l-67.4-113.7c54.5-35.4 88.4-84.9 88.4-139.7zm-466.8 14.5c0-73.5 98.9-133 220.8-133s211.9 40.7 211.9 133c0 50.1-26.5 85-70.3 106.4-2.4-1.6-4.7-2.9-6.4-3.7-10.2-5.2-27.8-10.5-27.8-10.5s86.6-6.4 86.6-92.7-90.6-87.9-90.6-87.9h-199V361c-74.1-21.5-125.2-67.1-125.2-119.9zm225.1 38.3v-55.6c57.8 0 87.8-6.8 87.8 27.3 0 36.5-38.2 28.3-87.8 28.3zm-.9 72.5H365c10.8 0 18.9 11.7 24 19.2-16.1 1.9-33 2.8-50.6 2.9v-22.1z"/></svg> package `pwr`. ] .pull-left[ **Power Analysis Relationships** `\(\uparrow \text{Power}\)` `\(\uparrow n\)` (holding `\(\alpha\)` and effect size constant) More data will give you a better chance of detecting differences between A/B `\(\uparrow \alpha\)` `\(\downarrow n\)` (holding power and effect size constant) `\(\alpha=5\%\)` gives you a greater chance of rejecting the null than `\(\alpha=1\%\)`. However, that also increases the chances of Type-I error. `\(\uparrow \text{effect size}\)` `\(\downarrow n\)` (holding power and `\(\alpha\)` constant) Hence, the higher the power/the lower the significance level/the smaller the effect size you want to detect, the higher the sample size you need ]